Lübeck: the Hanseatic Ex-Powerhouse

I had always wanted to visit Lübeck, captivated by images of its magnificent Gothic architecture. So, when an opportunity arose to make the trip, I seized it without hesitation.

This time, I won't dive straight into the highlights; instead, I'll take a more narrative approach. As is often the case, the best comes at the end.

Upon arriving at the terminus of the regional route, I was greeted by a bright, lightweight canopy of Hauptbahnhof Lübeck (the Central Station). It reminded me of a similar one in Kaliningrad. But, after all, the sheds of German train stations share a similar look, more or less.

The train station building turned out to be an impressive piece of historicist architecture (Neo-Baroque + Neo-Gothic + elements of Jugendstil), built in 1908 by architect Fritz Klingholz.

"Well, a promising start," I said to myself.

I needed to reach my hotel first. It was early Friday afternoon, and I still had work to do. I could have taken a bus, but after a three-hour train ride, I decided to stretch my legs and take a 20-minute walk. My path led through a calm neighborhood full of lovely yet modest villas and traditional German block buildings.

In every German city, one can find the so-called Stolpersteine ("stumbling stones"), and Lübeck is no exception.

These stones, as is well known, commemorate the victims of the Holocaust (the one above honors three families) and are placed near their last freely chosen place of residence, even if the building itself no longer exists.

After wrapping up work for the week, I decided to take a walk in the city. This time, I chose a different route, going through the eastern edge of the St. Lorenz suburb and later to the area in the northwest, where the city's fortifications once stood.

Certainly, there wasn't anything left; everything had been torn down a long time ago. But we'll get to that. I did manage to stumble upon certain ruins.

An abandoned factory, and judging by the asphalt of the former parking area, it hadn't been in use for about 15 years or so. Labels on the entrance gate indicated that it was once a facility belonging to the Vion Food Group. The Dutch meat processor left the German market in 2006.

Well, that's a common sight you can see practically anywhere in Germany. Here and there, there are ruins of factories dating back to the 19th century. These are typically listed buildings protected by the government, so no one dares to demolish them. On the other hand, there's usually no enthusiastic investor to breathe new life into them either. In big cities, the ruins are often converted into lofts, coworking spaces, hotels, and apartments. But in small towns or on the outskirts, such structures are destined to stand on the verge of collapse, waiting for what happens next.

The next building was a bit more shocking to contemplate. It's not every day I see a rather modern factory completely trashed like this. There wasn't a single intact window; the blinds hung awkwardly, as if after an airstrike. The loading bays stood wide open.

That was the facility of the Norddeutsche Fleischzentrale — another company specializing in pork processing — which left Lübeck in 2005 due to shifts in the industry.

"Germany is doing great!" popped up in my head.

Right next to this mess stood a true hidden gem of the neighborhood: the building of the St. Lorenz Bad (the St. Lorenz Bathhouse), judging by the bell next to the entrance, now evidently repurposed into a living space.

Cool, I like that.

The churches of the historical center were already within reach.

After crossing the railways, I proceeded to the area of the former fortifications...

...only to find a former harbor area. After the ramparts were demolished in the 18th century, the port took over the freed-up space. But in the second half of the 20th century, it struggled to adapt to containerization. Political and territorial shifts following WWII further reduced its importance, and its utility has declined ever since.

The Willy-Brandt-Allee runs through the area and ends in a rather bleak district. One might expect a street named after a former German chancellor to be located somewhere central, but here we have quite the opposite.

On the western side, there were a bunch of Lagerhäusern (warehouses), apparently waiting for renovation. Some of them are occupied by various venues—very much like in Berlin.

The crane that once served the warehouses and the railroad branch on this side was gone—only the crane rails partially remained. Despite the presence of a parking lot, the place felt completely deserted. You need to be extra careful and watch your step—unless you want to stumble upon the remains of the rails and take a swim in the Trave (local river) 🫠

Across the city channel there was another bad-looking industrial area with remnants of old buildings from the past century.

On the other side of the Wallhalbinsel (island), it was a bit more lively—people were out and about despite the dull, almost rainy weather, fishing,and not without some success, I must admit. Where the open-air museum Museumshafen Lübeck begins, I saw many docked boats and yachts, along with four absolutely stunning turret and portal cargo cranes made of riveted steel.

These cranes used to move back and forth along the riverbank, transporting goods between docked ships, warehouses, and train wagons positioned below.

All covered in rust, mud stains, and vegetation—undoubtedly unmaintained and inoperable for quite some time—they still stand as a stunning example of the technical marvels of yesteryear.

Like giant alien space invaders, they stood there—absolutely dominant. Cargo ships no longer visit the harbor, but the cranes still stand proudly.

The warehouse closest to the city had already been repurposed into a hotel, restaurant, club, and possibly even living quarters, with three additional floors added. Surely, all of these were listed structures, and it seemed only a matter of time before local businesses advanced the redevelopment further and took over the entire island.

I crossed the Trave via the Drehbrücke (Turning Bridge), another historic structure—swinging bridges like this are quite common in Germany. The bridge span rotates almost 90 degrees to let ships pass, with the process controlled from the bridge’s control post.

The bridge’s mechanics were still very much alive and operational. Through the windows of a small glass-and-steel Fachwerk cabin, I heard the sound of working machinery and saw a cup of coffee sitting on the operator’s desk.

Before entering the city, let’s set the expectations straight. Like many German cities, Lübeck suffered a devastating blow during World War II. In fact, it was the first city to experience the Allies’ new airstrike tactics, where planes came in waves: the first dropped explosives to tear off the roofs, and the second followed with incendiary bombs to ignite the exposed buildings.

On March 28, 1942, the city center—mostly made up of old timber-framed buildings—went up in flames like a matchbox. According to the German Wikipedia, over 300 people lost their lives that day, and more than 15,000 were left homeless. The Cathedral of Lübeck and other churches sustained heavy damage. The cathedral museum turned into a charred shell along with all its cultural heritage. Around 1,500 buildings were destroyed by fire, and another 2,000 were seriously damaged.

The city was later spared from artillery shelling, as the governor of Lübeck was wise enough to surrender without a fight.

The scale of the destruction can be seen in the photos from this article. Still, after looking at photos of other cities after the war, I can say I’ve seen much worse. For instance, Warsaw in Poland was leveled to the ground—there weren’t even a few walls left standing in what used to be densely built neighborhoods.

After the war, restoration began, reusing everything salvageable and following archived blueprints. However, some ruined and badly damaged buildings were demolished, including the cathedral museum. That seems strange to me, as photos suggest the museum building wasn’t beyond saving. The facades were still standing, and concrete-based reconstruction techniques were already known at the time.

Some buildings, on the contrary, were saved and restored even though they had just a facade left.

Despite the fact that the city was rebuilt, it still doesn't feel like Regensburg or Amsterdam—the replicas are easily distinguishable from the original buildings that still stand today.

Alright, enough rust, despair, and gloom—time to see some good stuff.

It was nice to see that a substantial number of brick Gothic medieval merchant houses with stepped gables had actually survived—or at least their facades had. Today, they are part of the UNESCO World Heritage.

I assume, however, that at least some of such buildings are replicas or partial replicas, possibly rebuilt using rubble and parts from their lost predecessors. In certain cases, these could have been only medieval facades, behind which there were completely modern buildings.

Brick arched wall braces like these can be seen in many old towns across Europe, but normally they are designed to support two adjacent walls separated by a very narrow passage. Here, however, the arches span a fairly wide street, which is rather uncommon.

Ever wondered why medieval buildings were built so tightly next to each other? Well, there are three reasons:

- Space within the city walls was limited.

- Due to poor thermal insulation, buildings needed to be close to each other to retain heat more efficiently.

- City taxes were often calculated based on the width of a building facing the street, which led to buildings being narrow, tall, and deep.

If you happen to find yourself next to an overly pompous medieval house, know this: it's probably a guild house—Lübeck retained several of them after the war. A guild house was essentially a meeting place, a venue, and a symbol of power for the members of a particular guild, such as a merchants’ guild, a sailors’ guild, and so on.

The house pictured above is Schiffergesellschaft (the Sailors’ Guild) house. On the medallions framing the entrance, it says: "Allen zu gefallen ... ist unmöglich" (It is impossible to please everyone). Such a wise statement.

And where have I seen similar medallions before? Ah yes, in another former Hanseatic city—Danzig.

I'm just kidding — they're actually called "Gänge" — small passages on the ground floor of certain buildings. This is another medieval relic and a distinctive feature of the city. The idea was that a homeowner could build smaller houses for servants behind the main house. These servants typically didn’t have access to the main building, so they had to pass through the arch to reach the inner courtyard.

Today, some walkways are still open to humble, quiet visitors, while others are strictly private and marked with corresponding signs, chains, or even closed off behind fences.

Each "Gang" has its own name, a corresponding sign, and a house number—for example, "Garbereiter - Gang 77" or "Bäcker-Gang 43", and so on.

There are also "Wege" 😂 — a more recent development of "Gänge". In this case, they were wide enough to allow an entire carriage to pass through. Such passages are more common in Germany, and many towns have buildings from the 19th century and later that feature them.

Now, looking at photos on Google of what’s behind the Sievers Torweg, I realize it was a total miss on my part not to go through. It’s just that I had an unpleasant experience before, entering a similar passage while exploring another town. That one led to private property, and I ended up having a rather unpleasant conversation with the tenants. So I was a bit hesitant to push my luck this time.

Well, a solid reason to visit Lübeck again!

By 9:00 PM on Friday, the streets were slowly starting to empty. Most people had either headed home or gone to the pubs. :)

In this part of the city center, there was the Marienkirche (Church of Saint Mary) and the Rathaus (Town hall), but they were basically surrounded by modern buildings. In front of the Town Hall stood a huge, ugly Karstadt building (how typical for Germany), now abandoned.

A typical post-war German city is such an architectural patchwork of old and modern buildings.

So, on my way back to the hotel after a concert (yes, I came to Lübeck for a concert), I took lots of photos as usual, but most of them turned out poorly due to the low lighting conditions. However, since I didn’t get a chance to pass by the Dom the next day, I'll share a few photos from my late evening walk.

The cathedral, like many others, gave off a skyscraper-like vibe: it stands 132 meters tall, towering over everything around it. Construction began in 1173 and lasted a long 74 years, finally being completed in 1247. What a project!

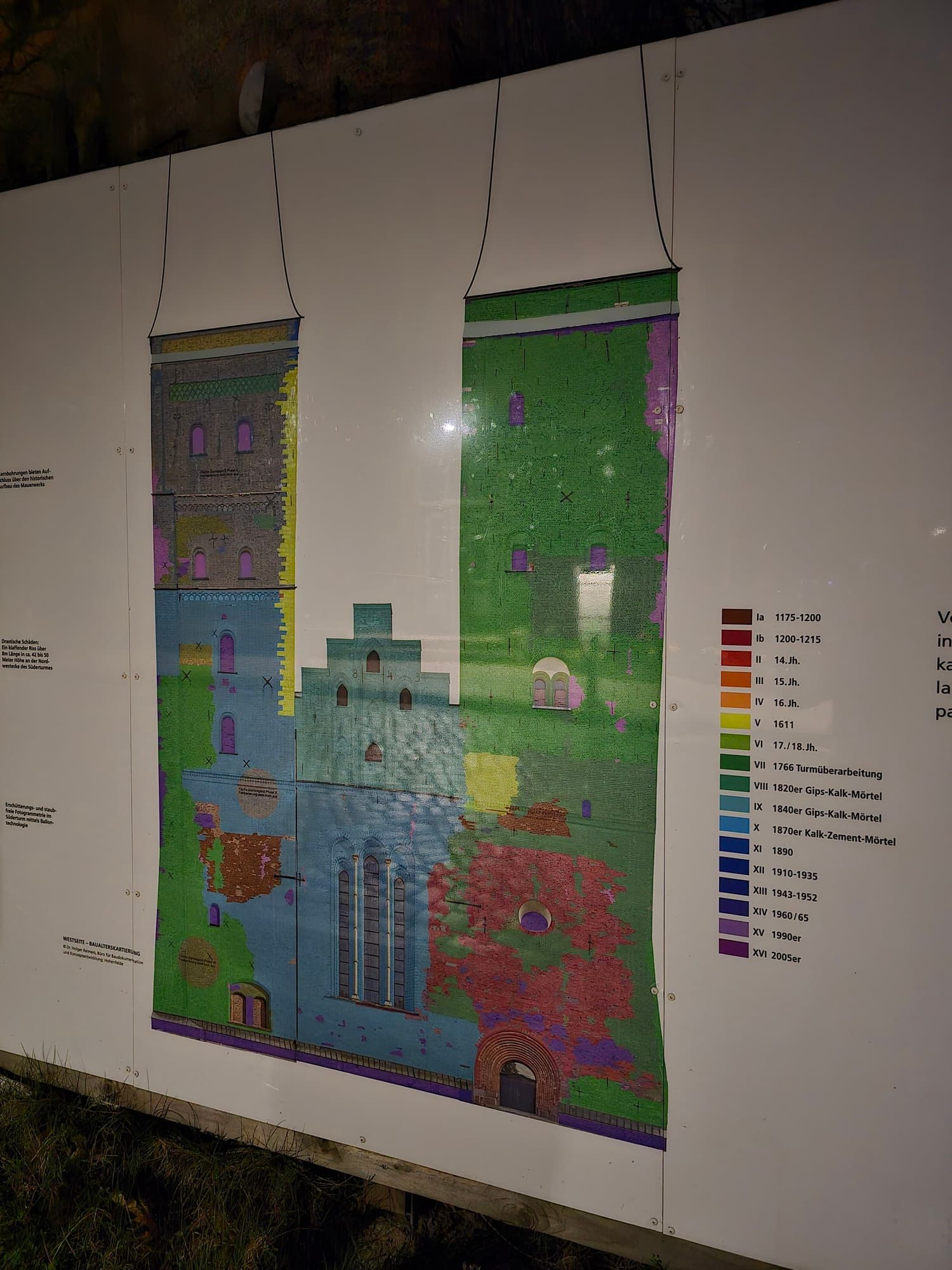

During World War II, the cathedral suffered heavy damage. Wars are always like that: some people dedicate their lives to lifetime projects such as this, developing cities, and then centuries later, some idiots descendants push buttons and let it all burn in minutes. The Lübecker Dom (Lübeck Cathedral) endured, however, and after the war, it was restored as mostly close to the original, with some modern modifications as well. In the photo, you can see the patchwork of bricks on the main facade: some bricks date back to the early period, while others are relatively new.

I’ll definitely make sure to go inside next time I’m in Lübeck.

Lübeck, as we know, had an extensive fortification system during medieval times. There were four main gates, two of which are still standing.

- Holstentor – the western gate, now the main tourist attraction

- Burgtor – facing north, still standing

- Mühlentor – the eastern gate, now lost

- Hüxtertor – the southeastern gate, also demolished

Each gate had several structures: the inner, middle, and outer passages with towers. These structures were connected by a system of bridges spanning the city moat. The area between the gates was protected by a defensive line of bastions and a city wall. In other words, there was a lot to see.

Today, all of that—except for the Holstentor, Burgtor, the "Katze" bastion, and remnants of the city wall—has been lost to time. Now, a question may arise: "Why? Why would the city governors allow such heritage to be lost? That's insane!"

Well, after a bit of research, I dug up the following reasons:

- The defense system, originally built in the 12th century, lost its significance due to military advancements and essentially became a burden.

- In the 19th century, a new urbanization trend emerged that favored wide, open spaces full of light and air. Roads were meant to be broad to allow traffic flow freely through the city. Lübeck didn’t want to fall behind—they wanted to stay modern.

- I bet the gates fell into disrepair fairly quickly, and no one wanted to finance the restoration.

Also, let’s keep in mind that mass tourism—which today benefits greatly from such heritage—wasn’t really a thing back then, as the means of transportation were still quite primitive.

So, after leveling the bastions, ramparts, and gates, a lot of new free space appeared. In the north, the space was taken over by harbors; in the middle, a sparse residential area emerged; and only in the south, where the Katze bastion still stands, undeveloped green area remained. If you look at Google Maps, you’ll notice that the line of the city moat’s bank has a sort of star-shaped outline—this is the silhouette of the long-lost ramparts still visible today.

Yes, the authorities undeniably made a huge mistake, as Lübeck could have easily rivaled other historic cities like Prague if the gates had been preserved. Nevertheless, it’s quite short-sighted to blame them, as they were guided by the trends and challenges of their own time.

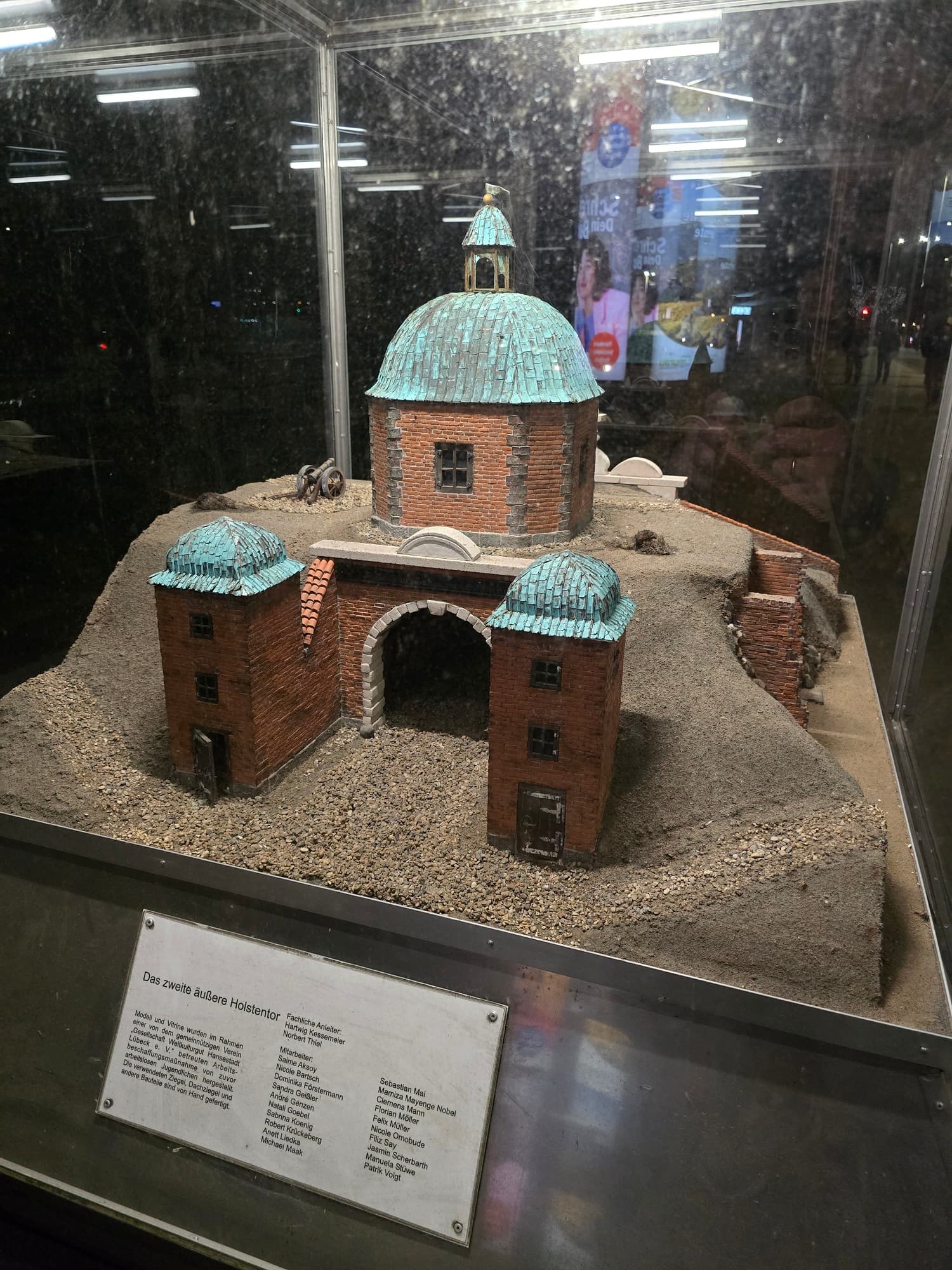

As a small token of courtesy to the now-lost historical legacy, a series of models of the gates have been installed here and there, giving tourists a glimpse of the treasures that once stood.

There are a couple of funny stories about the Mühlentor.

First of all, the middle section of the gate was removed in 1809, but later, at the end of the same century — in 1895 — a temporary replica of the structure was erected as the entrance portal to an industrial exhibition.

The replica was made of cheap, flimsy materials and didn’t last long. A photo of that replica exists, and it can easily be mistaken for a historical photo of the original Mühlentor.

Another story is about a military bunker disguised as one of the two towers of the outer section of the Mühlentor was erected by the Nazis in 1941. It still stands today, although unfinished.

I visited the Holstentor the next morning but completely missed the Burgtor—another reason for a return trip.

I still hadn’t decided what time to depart. I thought about selflessly leaving the hotel at 5:00 AM, walking to the city center to see the Holstentor (the primary objective of this trip) and taking some photos without the tourist crowds.

After waking up around 9:00 AM 😂, I took a shower and left the hotel.

Finally, I reached the place. Behold: the Holstentor. (Gates to Holsten) Such a beauty.

The gate is a massive structure consisting of two towers with pointed tops and a passage between them, constructed in far 1478.

On the field side, there is an inscription: "Concordia Domi Foris Pax" — a shortened version of "Concordia domi et foris pax sane res est omnium pulcherrima", meaning "Harmony at home and peace abroad are indeed the most beautiful things of all." This inscription dates from 1871.

The metal hooks on the facade were intended to hold sandbags, which would help minimize damage from projectiles hitting the building.

On the city side, there is another inscription: "S.P.Q.L." — "Senatus Populusque Lubecensis" in Latin ("The Senate and People of Lübeck"). This is a homage to the ancient Roman "S.P.Q.R." — "Senatus Populusque Romanus" ("The Senate and People of Rome"). The year 1477 is supposedly the date of construction (though that's incorrect—the correct year is 1478), and 1871 marks the year of the first restoration.

Along the facade, two decorative belts run with terracotta tiles. Most of the tiles depict flowers (lilies), but some also feature a two-headed eagle—the coat of arms of Lübeck—and two banner carriers.

Due to misakes made during the construction, the towers of the gate have developed a noticeable tilt over time. The southern tower leans to the west, and since there is no reinforced structural connection between the towers, they are also tilting toward each other.

In the end of the XIX century the situation worsened to the point that the structure resumed sinking and listing rapidly. Amid the wave of demolishing other "annoying medieval derelicts", a petition was raised in 1855 to finally tear down the last standing section of the Holstentor.

However, another group of citizens petitioned to save the building, and in 1863 the government decided to preserve the gates. Restoration was carried out in 1871.

By that time the building was in such a poor shape, that the restorers had to make some educated assumptions to fill the missing parts in. For instance, no one knew what the stepped gables originally looked like, as no reliable references existed (only a rather artistic, yet unreliable engraving was available), so the missing parts had to be rebuilt with fair amount of creativity. Similarly, the terracotta tiles on the facade, including the coat of arms, are said to be a quite free interpretation.

Unfortunately, the issue with the unstable foundations wasn’t resolved, so yet another round of restoration was carried out by the Nazis in 1934. They reinforced the building’s foundation with concrete but also introduced other changes, such as merging the floors of the northern tower, that was a rather drastic and crude intervention in the monument's structure. They also placed a swastika on the facade (which was stolen in 2005) and turned the gates into a museum celebrating the glory of the nation.

(☝️ We pretend not to notice the year on the door handle)

The final round of restoration took place in 2006, giving us the gates we see today.

The experience wouldn’t be complete without seeing what’s inside the building. In one of the rooms, elements of the gate’s defensive capabilities can be seen. The stone tray just under the window was intended for pouring boiling pitch onto the heads of unfortunate attackers, while the chimney was meant to keep the pitch hot. I say "intended" because the gates never actually saw any action.

But hey, formidable fortifications aren't just about doing actual damage—they’re also meant to intimidate, right? Maybe the imposing look of the gates alone was enough to discourage anyone from thinking about taking the city.

And to answer any questions about why the gun doesn’t match the window—the gun isn’t original to this spot; it was transferred from the Katze bastion. The ring on the wall was apparently used to cushion the weapon’s recoil.

The larger windows face the city, while the smaller ones are directed toward a potential enemy.

What we see today is actually just one of the four structures that together used to be called "das Holstentor."

There’s a whole story behind it. The defense system was gradually reinforced over time and then, as we already know, eventually torn down. Here’s the timeline:

- Initially, there was a gate (later known as the "inner gate") that stood directly on the bank of the Trave River, allowing people to pass through the city walls via a bridge (the leftmost structure). The year of construction is unknown, but it was built no later than 1376.

- In the 15th century, the existing fortifications were deemed insufficient, so in 1478 the middle gate (the one we see today) was built. Even at the time of its construction, the gate was already technically outdated.

- One hundred years later, in 1585, the outer "crooked" gate was erected about 20 meters away from the middle gate, at the location of the newly constructed city ramparts. This new gate had an intricate Renaissance-style facade facing the field and completely blocked the view of the middle gate.

- Another hundred years after that, in 1621, the second outer gate was erected as part of a second, newer line of ramparts.

- Sometime in the 17th century, the inner gate was replaced by a simplified half-timbered structure.

Then, over the course of a century, all gates except the middle one disappeared:

- In 1794, the half-timbered inner gate was replaced by a lattice gate.

- In 1808, the second outer gate was demolished.

- In 1828, the inner gate and the city walls were demolished.

- In 1853, the outer gate was demolished to make space for the railways (which no longer exist today either).

In the southern tower, there is a model of the middle gate with two parts swinging to the sides, offering a glimpse of the interiors.

The geographical situation of Lübeck allowed it to become one of the most important (if not the most important) cities of the Hansa trade union. That’s why the city desperately needed extensive fortifications.

However, another problem was the safety of sea transportation. To fight piracy on the Baltic, the city developed a strong military navy.

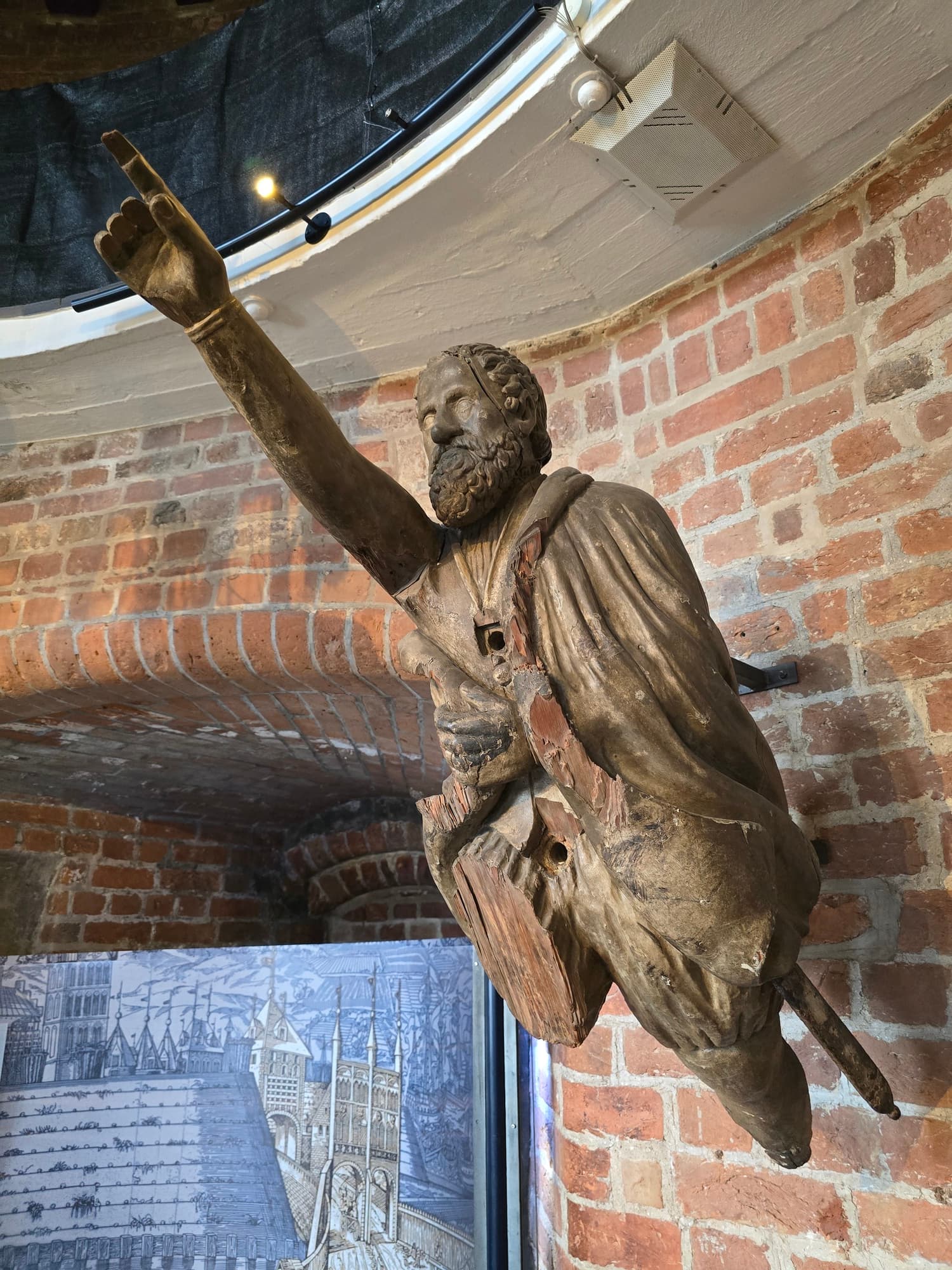

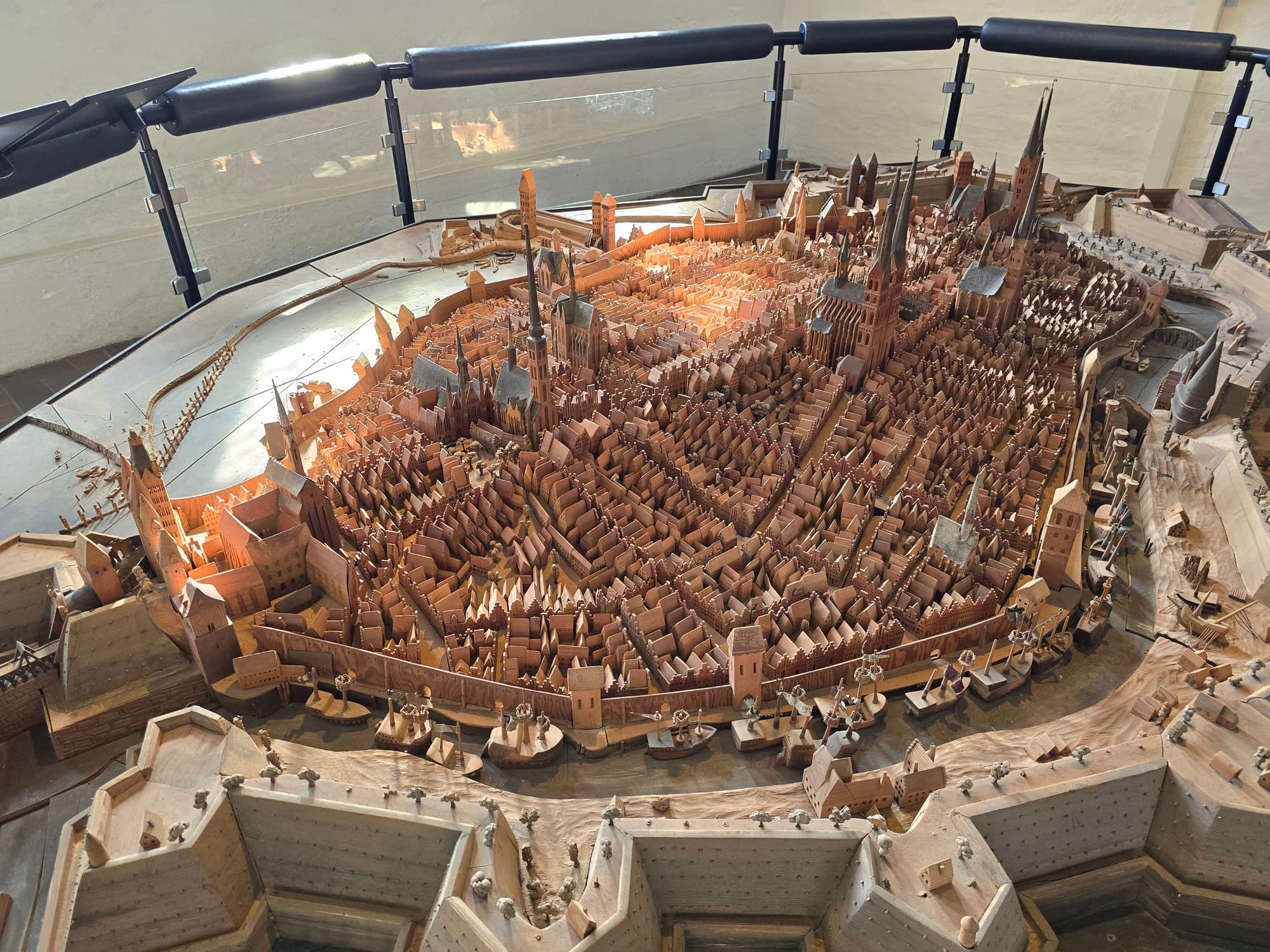

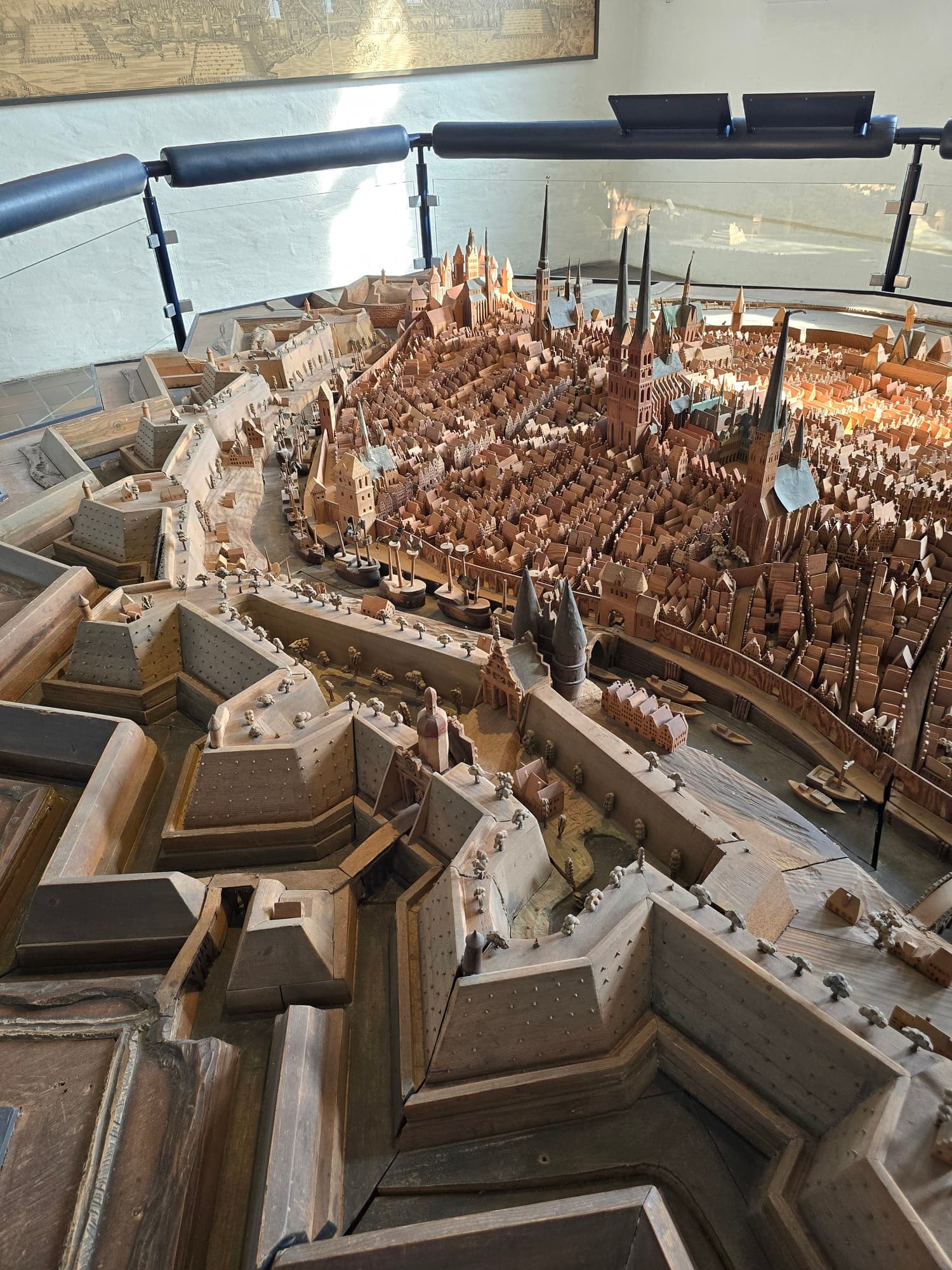

A true gem of the museum is a model of the city as it was sometime in the 17th century. The wooden model was made by scholars of that period and miraculously survived two world wars. The vertical scale is a bit off, though — the ramparts were never that tall, and the towers look like mini-versions of the Empire State Building, which isn’t scientifically accurate either.

The last room of the museum is dedicated to medieval justice and execution.

There, a 300-year-old torture rack was on display. Honestly, I had no desire to take photos, because it wasn’t some kind of fake prop created to amuse clients of a local restaurant. Real people were tortured and murdered using that tool.

On my way out, I told myself, "Alright, the primary objective of this trip was achieved, now onto the extra stuff!"

Right by the gate are the famous "Salzspeicher" — former salt warehouses, constructed between 1579 and 1745 to temporarily store salt from Lüneburg. Salt was an extremely valuable commodity, as it was used to preserve fish.

The buildings are in good condition, however, the northern Speicher experienced drastic modifications: a passage was cut right through the building. That seems like a wild thing to do to a historic building, but perhaps it was necessary to alleviate pedestrian traffic in that area.

I wouldn’t have had any idea where to go from there if I hadn’t talked to a museum worker at the Holstentor. It’s their job to look after visitors—and gosh, the job must be boring. So I guess at least some of them are willing to give you a small free tour; worth a shot to find out.

In my case, the lady gave me good advice on what else to see in Lübeck.

So, extra stop number one — Die Marienkirche (The Church of Saint Mary). I silently named it "The Grim Church," and let me explain why.

The first church on this site was built in the 12th century and was continually expanded over time. Then, around 1300, a new structure with two towers was erected. Its design was inspired by French cathedrals built of natural stone, but the decision was made to construct it using bricks instead. This choice proved successful, and many other churches in northern Germany were subsequently built following a similar concept. As a result, the Marienkirche is often referred to as "the mother of Brick Gothic churches."

The church had a long history, and its interiors used to hold a lot of precious artifacts accumulated over time. Almost all of them were lost during the air raid in 1942. The altar, the organ, numerous medieval wooden artifacts (Wikipedia says around 36), naval banners, and precious paintings — all were lost. It was a tremendous loss for Germany’s cultural heritage.

During the air raid, the bells rang loudly, swinging on the streams of hot air. Then, two of them partially melted and fell to the bottom of the south tower, smashing an epitaph and the brick floor into pieces.

There they lie to this day, serving as a reminder of the horrors of war.

You can imagine the sheer destruction of the building by looking at this photo:

According to the photo below, however, it can be seen that the vaults actually withstood the bombardment. What is also interesting is that the buildings behind the church on the left seem to be intact, yet they were later replaced by a shopping mall.

The restoration began in 1947 and was completed in 12 years. It was decided to keep the interiors simple, closer to the original roots, effectively concluding the nullification of everything that had been accumulated over the centuries. German restorationists and artists did an amazing job; however, of course, it’s not the same church it used to be.

The next notable artifact of the church is the famous Totentanzkapelle (Dance of Death chapel). It depicts a series of human figures with dark-skinned, eyeless corpses representing Death standing between them. Death speaks to a king, mayor, bishop, knight, merchant, soldier, monk, lady, girl, and eventually a child in a cradle. The main idea is that Death eventually comes for all of us, regardless of rank or social position.

What we see today is a printed photo of a medieval replica (around 1700) of an original painting from 1464 — essentially, a copy of a copy.

The painting was located in a dedicated chapel, protected by wooden shields during the time of war. During the air raid, the shields caught fire and collapsed, leading to the complete destruction of the chapel, the painting, and the organ. Ironically, a less meticulously protected chapel next to it sustained less damage.

The chapel’s vault was never restored, and part of a broken vault rib can still be seen sticking out of the wall today. The stained glass is a modern work, a courtesy to the lost medieval treasure.

Another interesting feature is the Astronomical Clock.

The clock is also a simplified post-war replica of the original one, which dates back to 1566 and was destroyed in the fire.

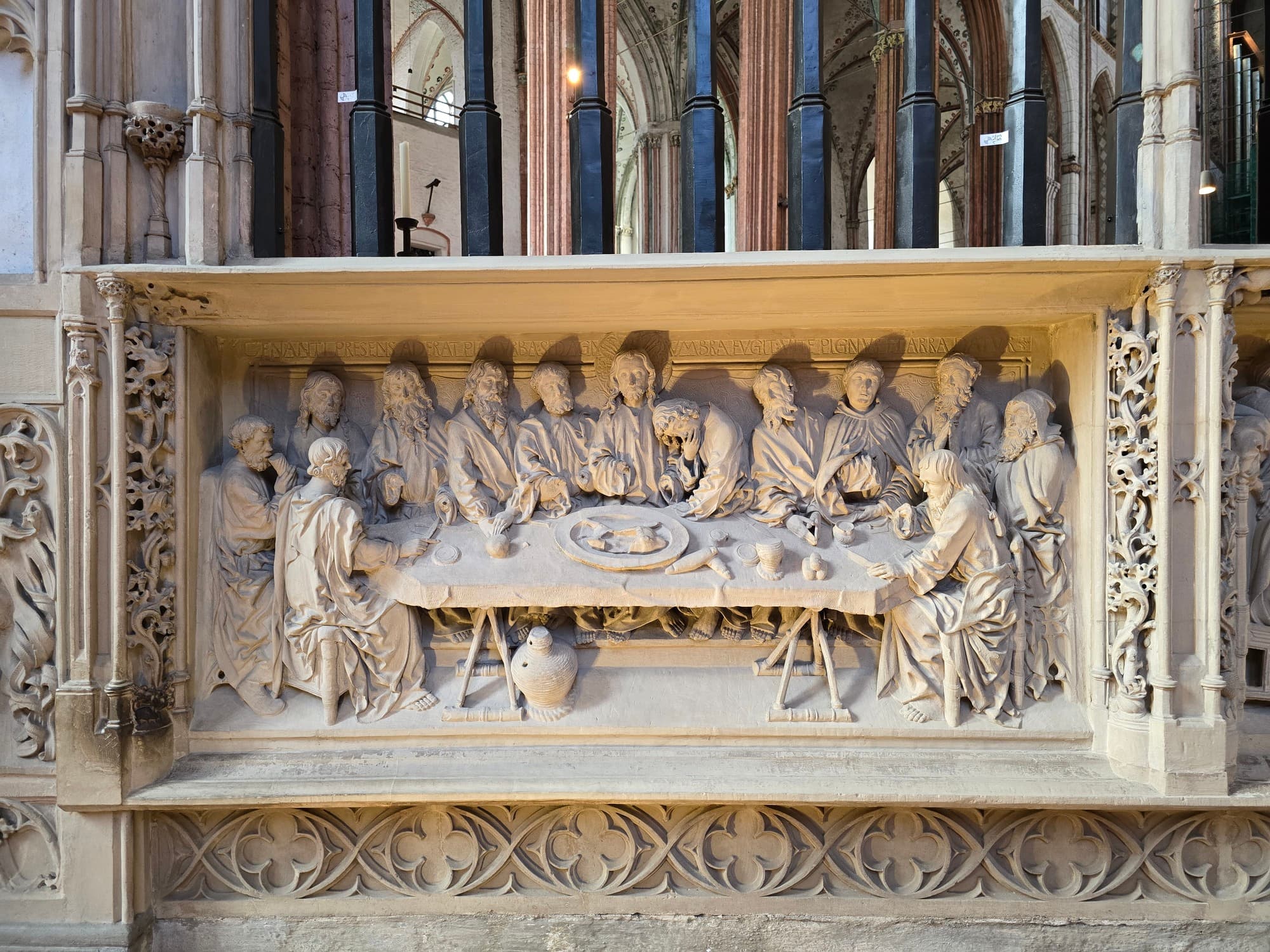

The wooden sculptures were lost to the fire, but the ones made of stone and marble were shattered into many pieces by the blast. The restorationists put them back together like a huge jigsaw puzzle.

After the restoration, the interior was redesigned, but a broken vault rib from the original interior was left to preserve the atmosphere.

Well, as we can see, after visiting this church, there is a lot to think about.

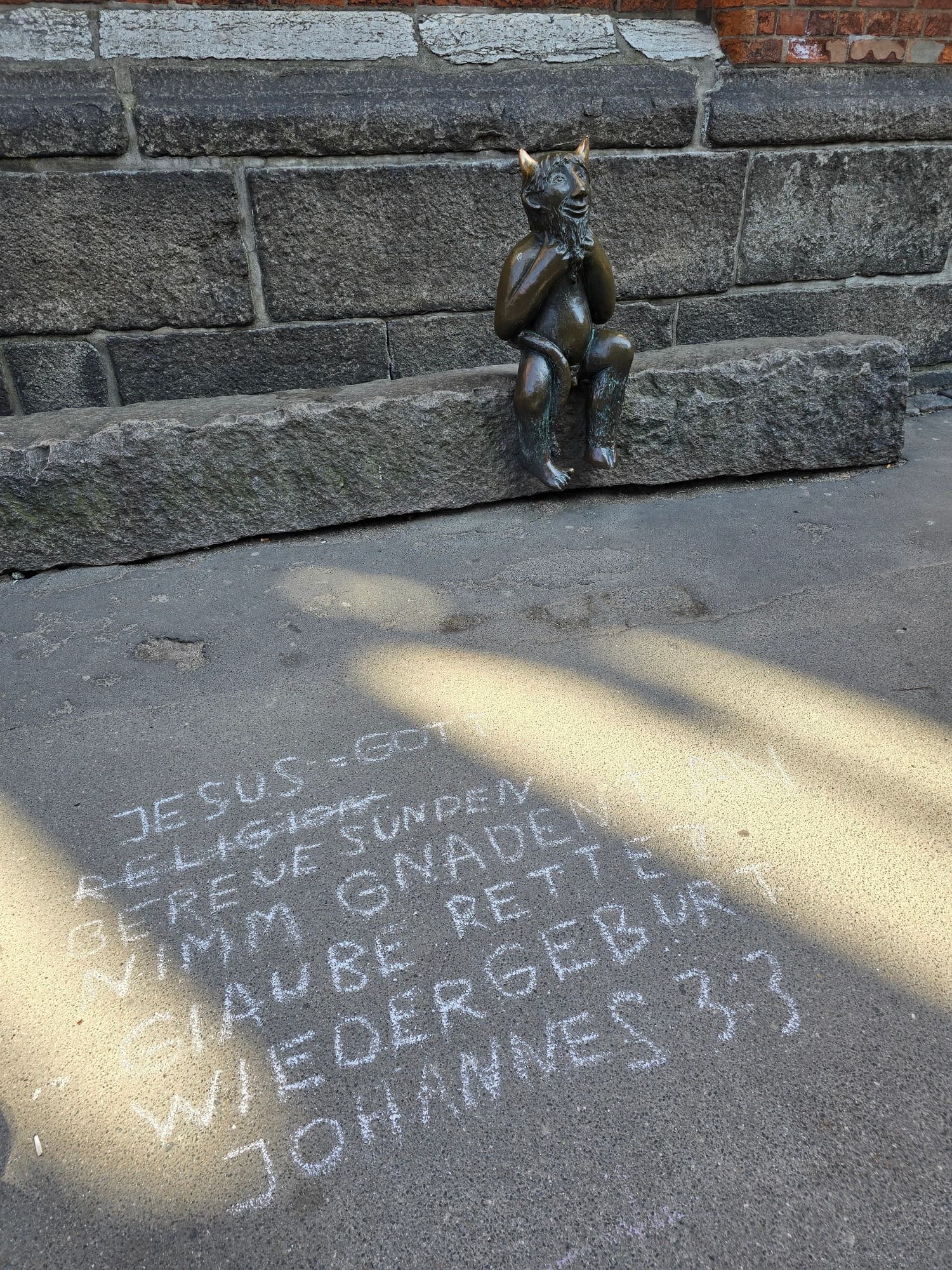

In the churchyard, there is a sculpture of a Teufel (Devil) that has become something of a mascot for Lübeck. There’s an urban legend attached to it: allegedly, the devil thought people were building a pub, and got angry when he found out they were actually building a church. In his rage, he threw the stone on which he sits today.

It was lunchtime, so I had to eat something. I chose a restaurant serving German cuisine, with prices above average, but I was won over by the fact that it was located in a historic building.

It was the Kanzleigebäude (Chancellery building), an extension of the Lübeck Town Hall built in 1485 and modified several times afterward. The building has an elongated profile running along Breite Straße. A notable feature is the 50-meter-long vaulted gallery on the inner side.

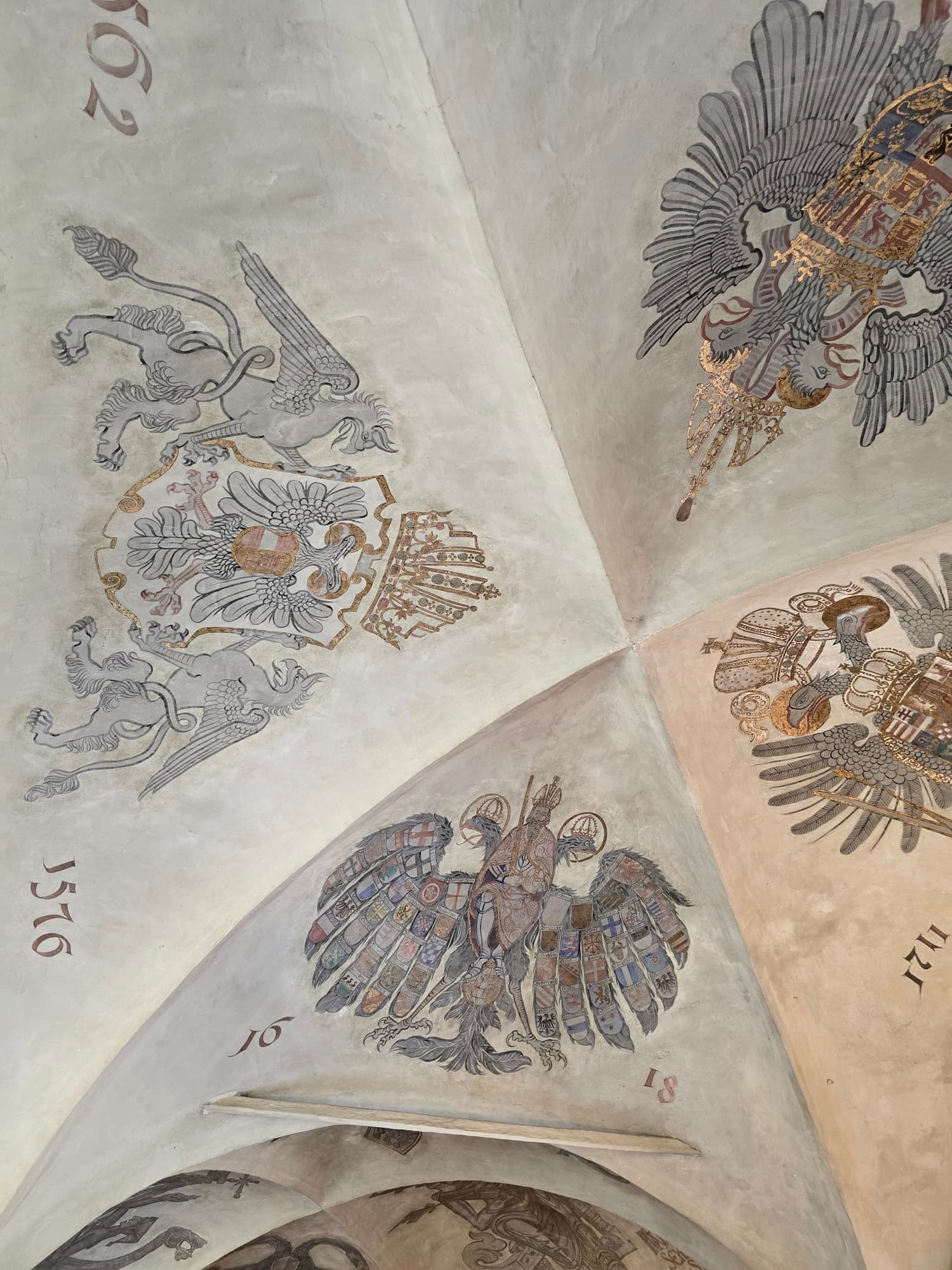

On the second floor was the Eagle Hall (Adlerssaal), with ceilings filled with paintings depicting various coats of arms from different periods of German history, as well as other eagle motifs.

Initially, I thought it was medieval, but after googling, I found out that it was painted quite recently — during the last renovation in 1939.

At the same time, the mosaic on the ground floor was created. It depicts wild cats running under the Sun. On the wall, there was the coat of arms (Wappen) carved of stone, probably medieval (until proven otherwise 😂).

Rathaus (The Town Hall) of Lübeck is a building dating from 1240. I won't even start describing its history and appearance, because after two fires, two wars, and several renovations and extensions, it’s basically a patchwork of different styles and epochs. Sealed and cut-through arches and doors, an incredible mix of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque, massive gables, and fake windows — this is what the Town Hall of Lübeck is.

It’s hard to miss the five amazing shield-like gables with fake windows and massive round holes (apparently made to reduce the windage of the structure).

The Town Hall, just like the Chancellery, has a beautiful arcade with a vaulted gallery on the inner side. The arcade is a mix of Gothic and Renaissance styles.

In the arcade, there is an interesting monument that says, "Die Heimat wartet auf euch" (The Homeland waits for you).

It’s dedicated to German people kept captive in camps of the U.S.S.R. and other countries after the war, who were still being waited for.

The arcade is partially taken over by the Niederegger Arkadencafé, which, in my opinion, is an aesthetic mistake.

I bet the owners of the café pay good rent to the city.

Too bad I missed my chance to visit the interiors of this truly majestic building! The guided tour starts on weekends at 13:00, but the number of tickets is limited, so guests need to arrive exactly at 12:00 to get one. I came at 12:50 and screwed it up.

Inside, you can find cute homages to the dragon theme and an absolutely astonishing staircase in the vestibule, decorated with black glazed ceramic tiles.

Mmmmmahhh.

The front door handles don’t fit comfortably in the palm, but just look at the character!

On the market square, I noticed an interesting small building.

Initially, I thought it was some kind of non-functioning fountain or a well. It turned out to be just a shed used to host some shopping stalls. It even has its own name — Kaak — and it’s not old at all. It’s a modern structure from 1987, built using medieval materials left over from previous market structures.

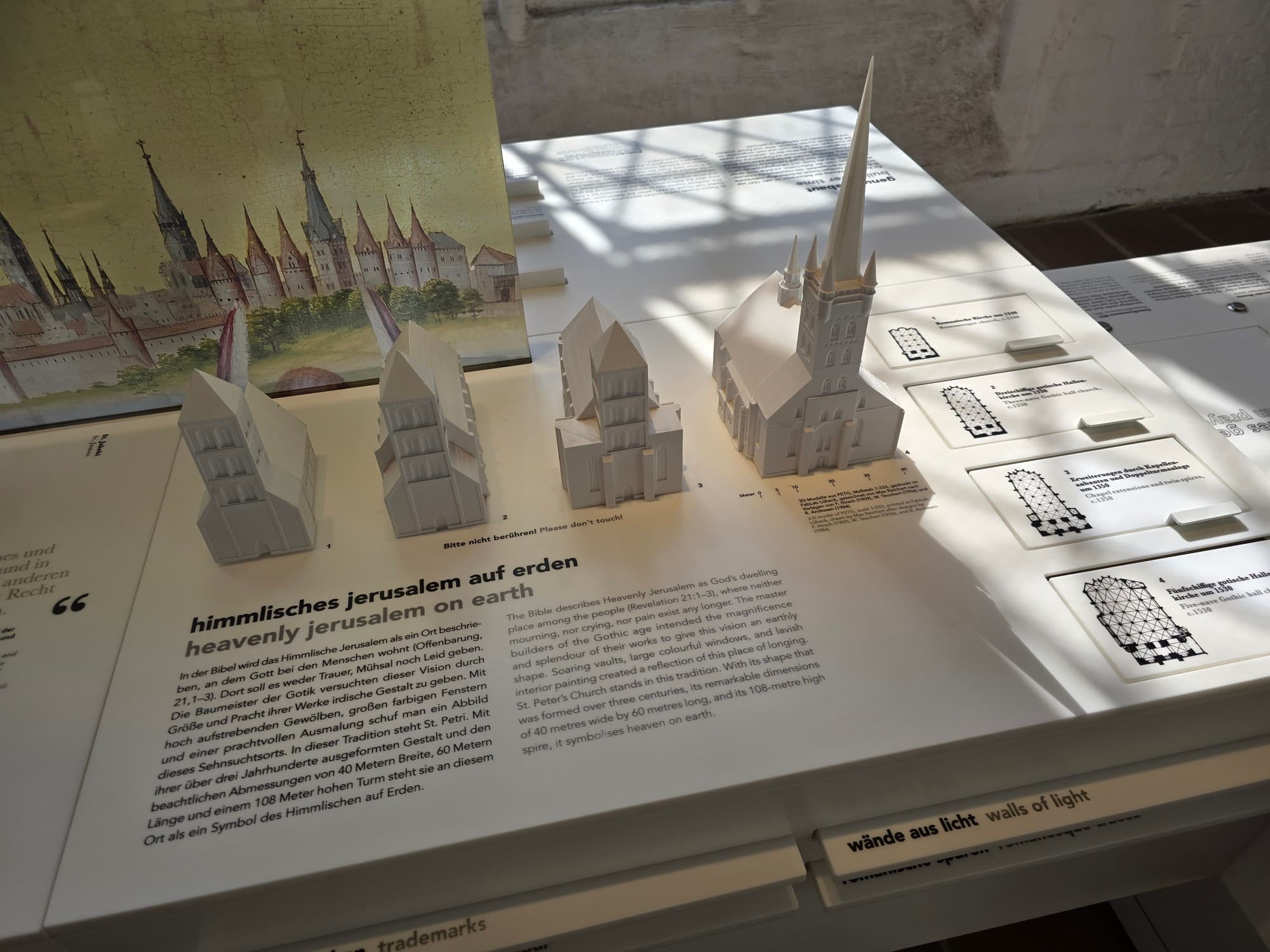

The next stop on my journey was St. Petri Kirche (The Church of Saint Peter). This is the only church that has its tower open to visitors.

The church was built around 1250, and it seems that initially it was planned to have two towers, as the Cathedral and the Marienkirche do. It was important because of the informal competition between the churches; however, probably due to a lack of funding, only one tower was eventually built.

During the air raid, the building was badly damaged and, just like St. Mary’s Church, lost all its interior as well as the spire.

However, it seems that the naves survived and did not collapse.

The building remained in disrepair for quite a while and eventually lost its entire congregation.

It was used as a warehouse, and there were discussions about what to do with it.

Later, it was decided to use it partially as a church and partially as a cultural center and venue for hosting thematic events.

Restoring the interiors to their pre-war state was unimaginable, so the walls were simply whitewashed, and the whole space was kept very simple and airy.

The remnants of the original paintings were preserved where possible, and they fit very well into the modern concept.

The epitaphs of the church are treated quite casually; for instance, one of them now serves as the floor of the in-house cafeteria.

Well, it’s said that the majority of them are no longer traceable anyway.

There is a small museum walking guests through the history of the church.

The St. Petri Church is the only church that has its tower open to visitors.

And while visitors get a short cardio workout climbing up, they are cheered up by the unique humor of the hosts.

At the very top, a spectacular view of the city is waiting.

From there, all the key landmarks of Lübeck are plain as day.

Before leaving this part of the city, I captured an iconic view of Lübeck’s riverbank.

The shot was taken from the middle of the Liebesbrücke.

The last church to visit that day was St. Jakobi Kirche (The Church of Saint James).

The history of the building is a bit less dramatic because it survived the bombing untouched.

It was founded around 1300 as a church for sailors and was initially planned to have... two towers again.

There is evidence of this in the way the bottom part of the building is constructed.

The spire of the church turned out to be problematic: in 1375, a quarter of it was blown away by a hurricane, and it was then partially dismantled and rebuilt.

Later, in 1901, it was struck by lightning and burned for a while.

Eventually, the spire received its notable feature — four balls on the corners, somewhat mimicking the turrets of St. Petri’s tower.

Thanks to surviving the Second World War, a lot of the original interiors have been preserved.

The church hosts one of the two original pre-war organs of Lübeck.

There are also intricate paintings on the wooden ceilings.

Another distinct feature is the carved wooden parts of the choir stalls, shaped like funny faces and animals.

But I hadn’t come there to see the medieval woodwork — I was looking for a boat and a chapel dedicated to sailors who had perished at sea, as advised by the museum worker at the Holstentor.

The rescue boat belonged to the vessel Pamir — a four-masted barque that sank during a terrible hurricane in 1957.

The ship listed dangerously due to sails not being reduced in time, as well as hatchways left open. Then the unsecured cargo shifted, causing the ship to capsize and sink.

Of the 86 people aboard, only 6 survived.

It is said that the accident marked the end of the use of sailing ships for commercial freight.

The boat looks severely damaged, with ruptures and holes below the waterline, and the stern completely broken off.

I can only wonder how it managed to stay afloat.

Initially, I had no plans to visit the Heiligen-Geist-Hospital (The hospital of The Holy Spirit), but it happened to be right next to St. Jakobi.

However, as soon as I entered the building, I immediately realized that I was right to stop by.

The hospital was founded in 1286 and is said to be one of the oldest social institutions in the world.

Inside, there was a foyer with beautifully decorated vaults and quite well-preserved wall paintings.

A highly detailed model of the hospital is available for visitors.

The main hall, where the beds used to be, is now used as a museum and a venue for hosting various events.

Parts of the hospital, such as the nursing and retirement homes, are still in use today.

It was time to hit the road, as my train was leaving in half an hour.

I only briefly visited the Hansamuseum.

The complex is an interesting mix of historical and modern architecture, offering a view of old Lübeck’s port.

The Burgtor was just around the corner, but unfortunately, I was already pretty tired after a long day, so it completely slipped my mind to pay it a visit. :(

On my way back to the train station, I saw good examples of new buildings mimicking the historical style.

Some of them fit in quite well.

Lübeck didn’t disappoint me. It’s a city full of history, tragedy, and life — totally worth visiting.

With such limited time, I couldn’t uncover it all; I still need to see the Burgtor, the Hansamuseum, and the Cathedral