Duisburg: Germany’s Detroit

I never planned to visit Duisburg in the first place, but I had to travel there from Amsterdam to put my family on the train to Berlin, leave the car at the parking lot and then travel back by bus for a few extra days. I didn't expect much, because I've heard many industrial cities in Northern Rhine-Westphalia were decimated by the war, rebuilt in a hurry and after the economic shifts started to decline. Duisburg is like that, yes, but it still has good stuff to show.

Next to the parking lot, where I left my car, stood the Central Railway Station. This is basically the first thing people see when they arrive in Duisburg. The station was built between 1931 and 1934 as a replacement for it's eariler predecessors from the period when the railway network was still private. Since the main building was erected at the same time as the other stations in Düsseldorf, Königsberg and Oberhausen, they all share the same architectural vibe.

The station is having difficult times, started from when it was temporarily downgraded from a hub into a stop point, and then back. The metallic canopy shows signs of wear, is partially torn down and according to the ongoing renovation plan is to be replaced with a new, modern one.

German Wikipedia says there had to be paintings on the walls of the interior, but they were painted over a long ago, and today there isn't much to look at inside.

An office building was erected on the square in front of the train station.

Despite how strange it seems, the building does not at all conflict visually with the surroundings. I always find it fascinating, how well steel-and-glass structures go together with the historical brick buildings. I think the key factor here is to keep the same lines and proportions, avoid placing round-shaped buildings next to square-shaped ones.

I took an e-scooter and headed straight to the river bank, because I've heard Duisburg was famous for it. The first thing I saw was the Ludwig Forum - an open-air event venue located where the buildings of Hermann Ludwig Land- und Seetransporte AG company used to stand.

Judging by google maps view the facitily was pretty large. There are still some windowless warehouses left standing by the river, as well as two abruptly looking leftovers that used to hold staircases, and now serving the exhibition purposes.

Large industrial scales left in place give the venue a special charm.

At some point I've figured, that since the region is called Rhine-Westphalia, the Rhine river must be somewhere close. I quickly checked the google maps and found out, that the river is just a few kilometers away. I switched the e-scooter for a bike and decided to take a detour.

I rode past the industrial area on the south-west side of the city, passing by massive, cyclopian loading bays.

The facitilies looked damn impressive, making me understand why some people love industrial architecture so much. I wonder though, when was the last time the bay doors were used?

After a while I've reached the river. Behold! The Rhine!

Well, it was just another river, pretty calm and not very breathtaking. I've been on Elbe, and now I've seen Rhine, checkmark.

After a short break I've decided to head back to the city.

Just in front of the forum stood the harbour with the rails still in place, now part of the pedestrian promenade. Surprisingly, the rails were not dismantled and scraped during the renovation, and now serve as a prominent remnant of the city's industrial past.

Besides the rails, the harbour still preserves a lot of other industrial equipment, such as cranes and warehouses. The cranes stand just next to the modern office buildings, which looks a bit surreal.

The old warehouses were also converted into office buildings and coworking spaces. Some of them bear marks of drastic conversion, while the others look pretty well preserved, at least from the outside.

The city didn't always have the harbor as it is today. In the X century the old town was located on a strategic place where two rivers - Rhine and Ruhr, met. Rhine used to make an extremely steep curve in that area without any apparent reason, so no wonder that around the year 1000, after a series of intense floods, the river changed it's flow to naturally straighten itself out. The old town was cut from the waters and could no longer serve as a port.

This event triggered the decline of the city's economy. However, the city residents didn't give up and dug a series of chanels in order to reconnect the city with the river. One of the channels is now know as the harbour of Duisburg. Also, the port was moved further to the north, to the area of the current Ruhrort.

It's a good lesson that teaches us never to give up.

The building of the Regional Archive really stands out. Even when I was driving into the city on a highway, I could see it from afar. I thought "What the hell is that? It's the tallest badass silo I've ever seen!"

When I came closer, I've noticed the windows were bricked up and so I assumed it was an unfinished conservated redevelopment of some kind. Only later I've discovered it was done on purpose, to uphold certain conditions inside. Also turned out, the tower erected at the center of the former granary is a modern one, it was built in 2014 to hold different kinds of valuable historical documents, recordings and other materials.

Here's a historical photo of the damaged granary, depicting how it looked like during the Second World War.

Both the tower and the window seals have a subtle brick pattern only visible from the close distance.

It's a nice detail that doesn't let the facade look cheap.

The red waivy building is also a part of the complex, it was supposed to be decorated with bricks as well, but due to lack of funding it was covered with simple plaster and painted red.

I am no expert, but haven't two recent World Wars, that happen to be the most distructive ones so far, taught us, that any building that has vaults full of valuable documents should not protrude above the ground as much as possible? Ideally such a building should be designed as underground facility and preferably located outside of the city?

I guess the city management desperately wanted to put the old granary to good use, and the architects gambled the humanity learned the lesson, that the next mass-scale conflict never happens.

I hope they were right.

Partially preserved medieval city walls of Duisburg is still a remarkable sight, even after all these years.

According to the schema I found at archaeologie-duisburg.de, the city still has 11 towers of various sizes and degrees of preservation left. One tower even has a restored wooden tiled roof.

As this schema shows, the most intact parts of the fortification are located on the north-east side of the city (marked with bold black lines).

Despite the fact, that not a single city gate remained today, the medieval walls of Duisburg are rumored to be the longest ones still standing in the entire NRW region.

It's clearly seen, that at some point some sections of the city walls were incorporated into the buildings standing close to them. It's a normal practice, this is how the medieval city walls of Berlin survived: they were parts of the buildings only discovered during the rubble demolition after the air raids of the WWII.

Also, by looking at the difference in brick condition it looks like some sort of repairs were carried out not earlier than the 19th century.

However, this is only my speculation, I should probably dig deeper into the history of the city.

In every city where I see the remnants of the medieval past standing next to the modern buildings, I always feel it to be bit bizzare and surreal.

I keep thinking of guardians who used to stand there on the watch, looking into the distance, waiting for the enemy to come. What would they say, if they saw their former post now desolated, half-dismantled, with gunports and embrasures standing face to face with the windows of a modern glass-and-concrete building?

Before we continue with sightseeing, I think it makes sense to talk about the modern history of the city.

In the middle of the 19th century the city of Duisburg was a major industrial center. It began as a logistics hub and tobacco/textile manufacturer, but later shifted heavily towards chemicals, coal mining and steel production.

It was a fine, well developed town with good architecture that could compete with cities like Amsterdam or Hamburg.

The success of the city attracted many people from all over the country, and the population grew rapidly.

Of course, all that made Duisburg a major target for air bombing during the Second World War.

The official sources hold records of around 300 air raids on the city, some of them happening on the daily basis. At the beginning the spirit of the city's inhabitants was high, projecting a sense of unity mixed up with nationalistic bravado, so common for a nation that just entered the war. People were telling each other "It's okay, we rebuild and we retaliate, crush the enemy together."

Soon enough the harsh reality hit the people. In the end, desparate and hopeless they were left with nothing. "There are ruins everywhere. Another building burned down last night, nobody cares anymore."

Nevertheless, after the war the city was rebuilt, and the industrial production boomed. However, after the government decided to move away from coal mining, and also due to the development of the container shipping (which the harbour could not accommodate), the city's economy started to decline once again.

It all started with a monastery, that doesn't even exist anymore. But the historical twist around this place is quite interesting.

So, in 1265 The order of Minorites was generously given a place to build their monastery in Duisburg. Minorites were well known for their ascetic views, so the monastery had a simple church, a hospital and a few other non-intricate buildings. In 1774 on the place of the monastery buildings another church was erected - The Church of Our Lady (Liebfrauenkirche), a much bigger one, and in 1896 the Minorites church was turned into a passage to the new building.

So they stood next to each other: the old and the new church, side by side.

However, the history has put everything on it's place once again.

The Church of Our Lady received massive structural damage during the WWII. According to the photos, the building still retained the tower and the walls of the nave, yet the building was completely torn down.

I travel a lot through the country and abroad, and it always baffles me how selective the people were about preserving certain damaged buildings or dozing them down. I've seen churches demolished only because they've lost a nave or two, and I've also seen marvelous examples of buldings assembled back brick by brick, even when there was just a single wall or two still standing. I guess the decisions were being made by different people under different circumstances, and the historical role of each building played a crucial part in it's final destiny.

The Minorites church was badly damaged as well, so in 1961 a new building with additional annexes was erected on it's place by the order of Karmelites. The new building tried to reuse the remnants of the Minorites church, such as the western portal, the eastern nave and the crypt.

The Karmelites left their monastery in 2002, and the complex stood empty for a while. The church was once again formally attached to the resurrected (in a different style) Liebfrauenkirche that stood several blocks away.

Quite complicated and sad, isn't it?

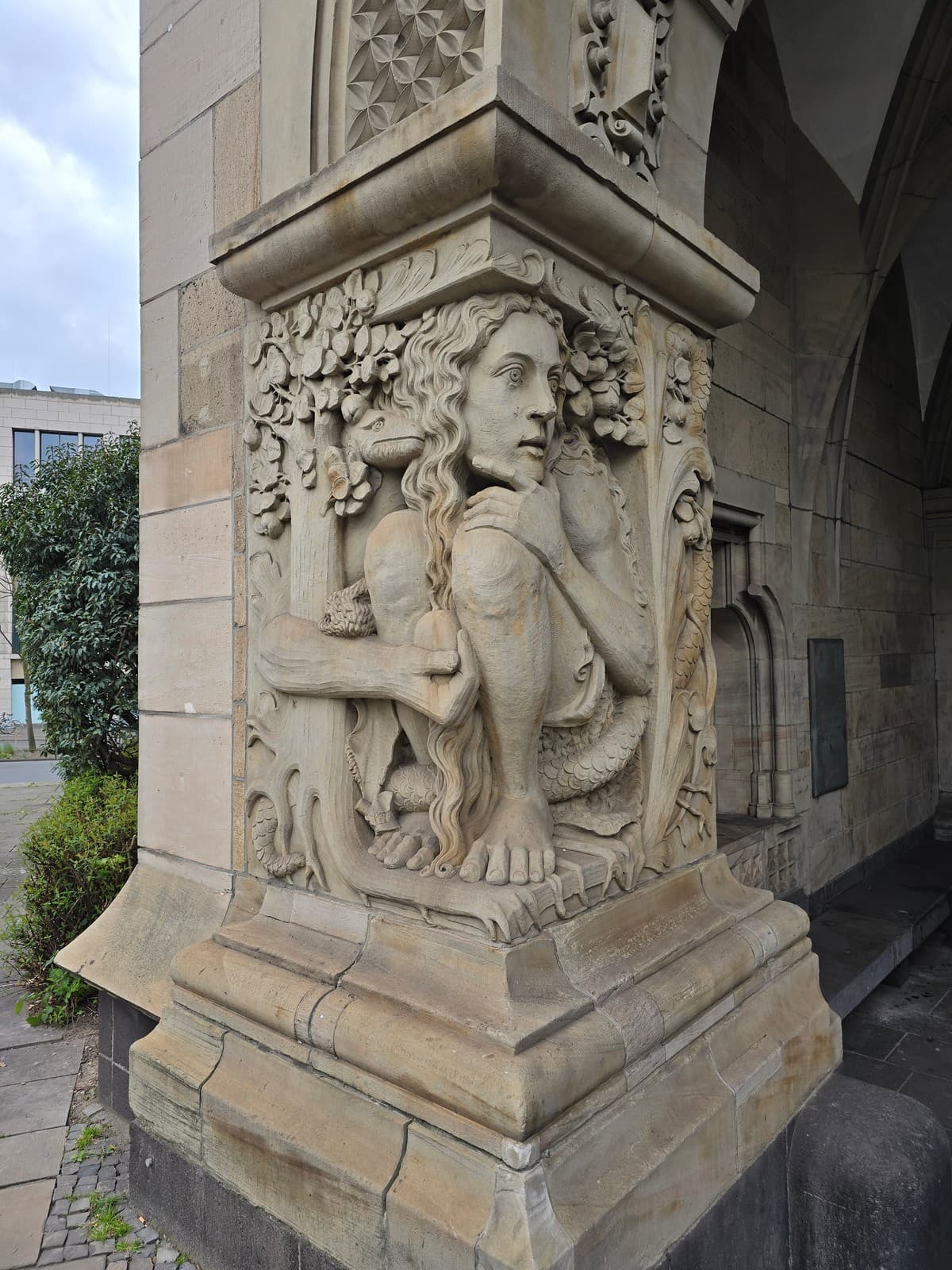

The City Hall (Rathaus) is another prominent sight in Duisburg. Constructed in 1902 by Friedrich Ratzel, it replaced the old city hall, which in it's time replaced the castle that once stood on the Castle Square (Burgplatz) and burned down in the middle ages.

The square, once a place of the city's pride, has lost it's importance today and now serves as a parking lot. The area feels disconnected from the rest of the city, with the most of the business and social activity shifted to the east, in the direction of the train station. This isn't a unusual phenomenon for cities that suffered from the WWII and later rebuilt with a different layout: the majority of the pre-war buildings were either destroyed during the war, or demolished later. Some of the streets don't even exist anymore.

Just as the square today, the building of the City Hall is a bleak image of it's former self.

The City Hall was severely damaged during the WWII. It completely burned out, loosing the roof, the pinnnacle of the tower, and eventually the baroque gables. The photo below clearly depicts that the gables survived the bombing, but since there was no roof to support them strucuturally, they were probably later removed to prevent collapse. The gables were later restored, but in a simplified form.

Despite certain losses, the City Hall still has a lot to look at. Check out the stunning sculptures on the facade!

Two of them, located near the arch, depict Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Eve holds The Apple, taken from the Tree of Knowledge. The Snake looks a bit sad, I wonder why.

There is also the statue of the knight Roland on the northen facade, that survived the smash of the hammer of war. Statues of the Roland - a kinght with a sword and a shield from the Song of Roland - is a popular motif in many german cities, it can be seen all over the country. It symbolizes the city's independence of law and trade and, eventually, freedom.

What a nice suprise it also was to find the plaque dedicated to Immanuel Kant, located under the Hall's arch. A pair of young people was sitting next to it, and I've asked them to move for a bit so I could have a chance to take a photo.

The plaque got my attention, and I immediately recongized it, because there was a copy of it in Königsberg, which is now exposed in the city's museum:

On the plaque it says: "Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and the more steadily we reflect upon them: the starry sky above me and the moral law within me."

Next to the Castle Square, which is located in front of the City Hall, there is also the Market Square behind it. In the medieval times it was an important place for trading. Today it's just another free space, not really used for anything special. The destruction of the buildings around the square made the archeological excavations possible, so now we can look through the archeological window to contemplate the basements of the medieval market hall once stood there.

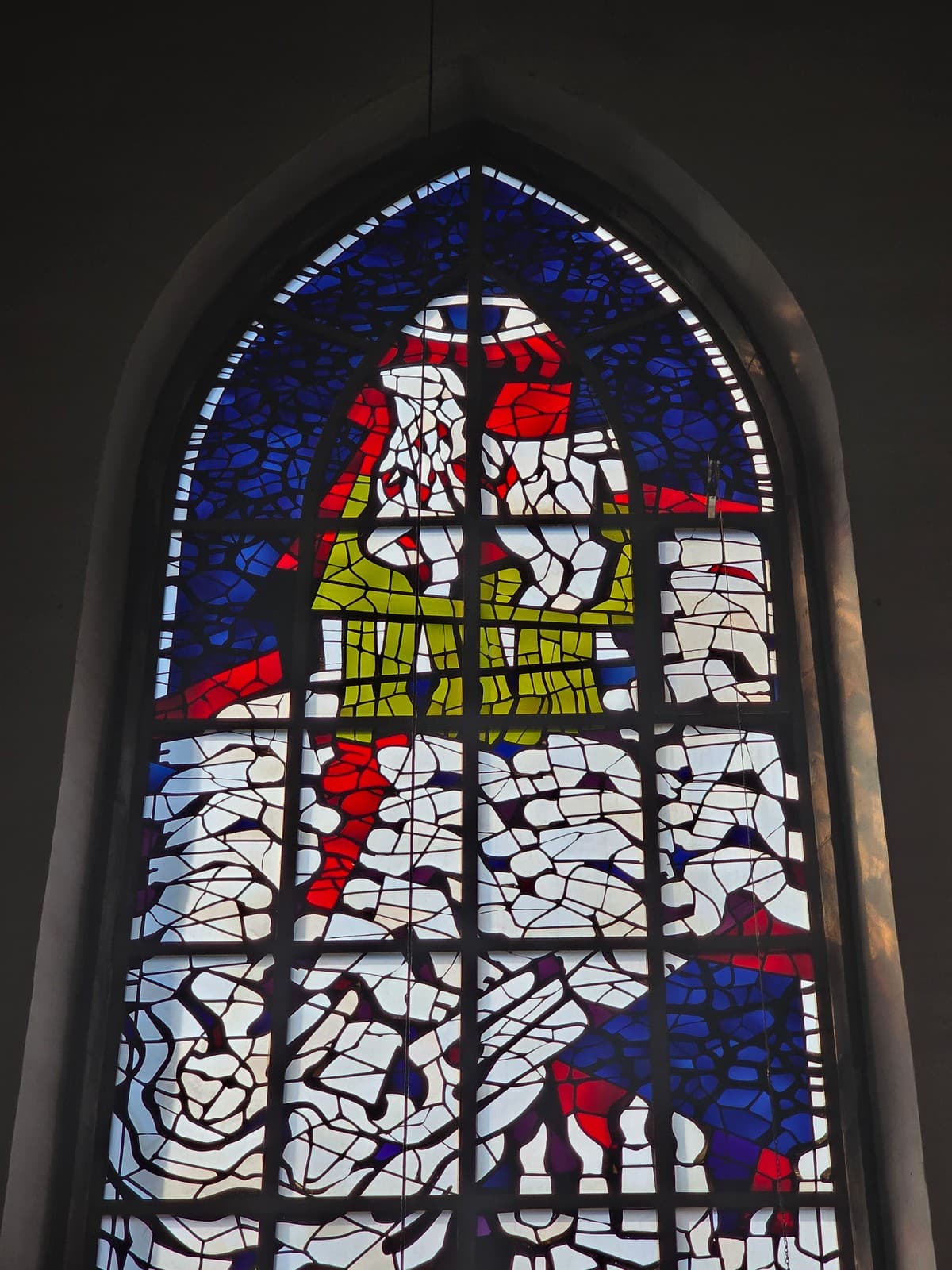

I was slowly getting tired, and still had much to cover. But it would be a mistake to miss an opportunity to look into the Duisburg's main church: the Church of Our Saviour (Salvatorkirche).

The church, as usual, has bold history. The very first wooden chapel was erected in 893, and there was archeological evidence of that. Somewhere in the XI centry the wooden church was replaced with the Castle church, which made total sense, because, as we already know, the castle was located nearby. That church was soon replaced with a roman basilica, the remnants of the basements of which have also been discovered.

In 1283 the devastating fire swallowed the castle and the church alltogether, and in 1316 the Teutonic Order laid the foundation stone of the church we see today. The construction has been completed in 1415.

Minorites, Karmelites, Teutons - so many christian orders left their mark in the history of Duisburg! Even the city itself has originally roman roots.

The tower spire survived four stages of reconstruction. It burned two times (caused by the strikes of lightning) and was rebuilt. The last time the spire was lost during the air raids of the WWII, and never resored ever since. That's why the tower looks a bit weird today, with it's flat top.

When I entered the building it was lovely and calm inside. I like visiting churches when the sun is setting or just rising, because in times like that there is a chance to catch stunning light effects from the stained glass windows.

At the time of my visit the interiors were being used to present an exposition, something about stuff made by children. Shortly after a priest approached me talking in german. At first I thought he wanted to tell me about the exposition, explain it's purpose. However, after we switched over to english, I realized that he was apologizing for the mess the exposition made. He told me he didn't like it at all, it wasn't his decision to have it there: some people just came and told him to host it.

The exposition was kind of nice, honestly, but I've decided not to argue.

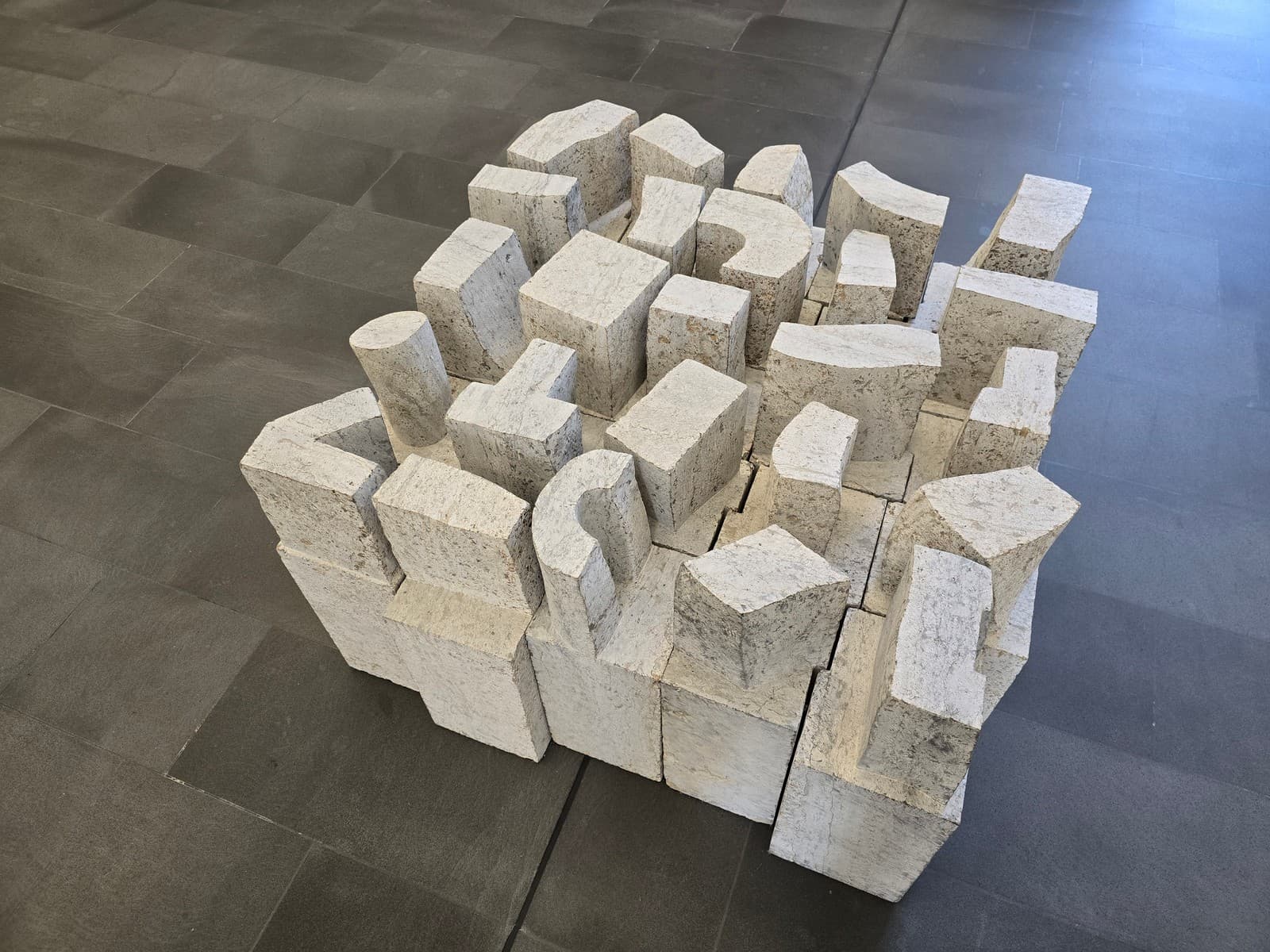

Inside and outside the church the decomissioned pinnacles of the buildings were exposed.

The last stop on the line was the Museum of Contemporary Art Küppersmühle. I approached the place from the south, walking through calm neighborhoods. The sun was shining once again, and the area seemed lovely and peaceful.

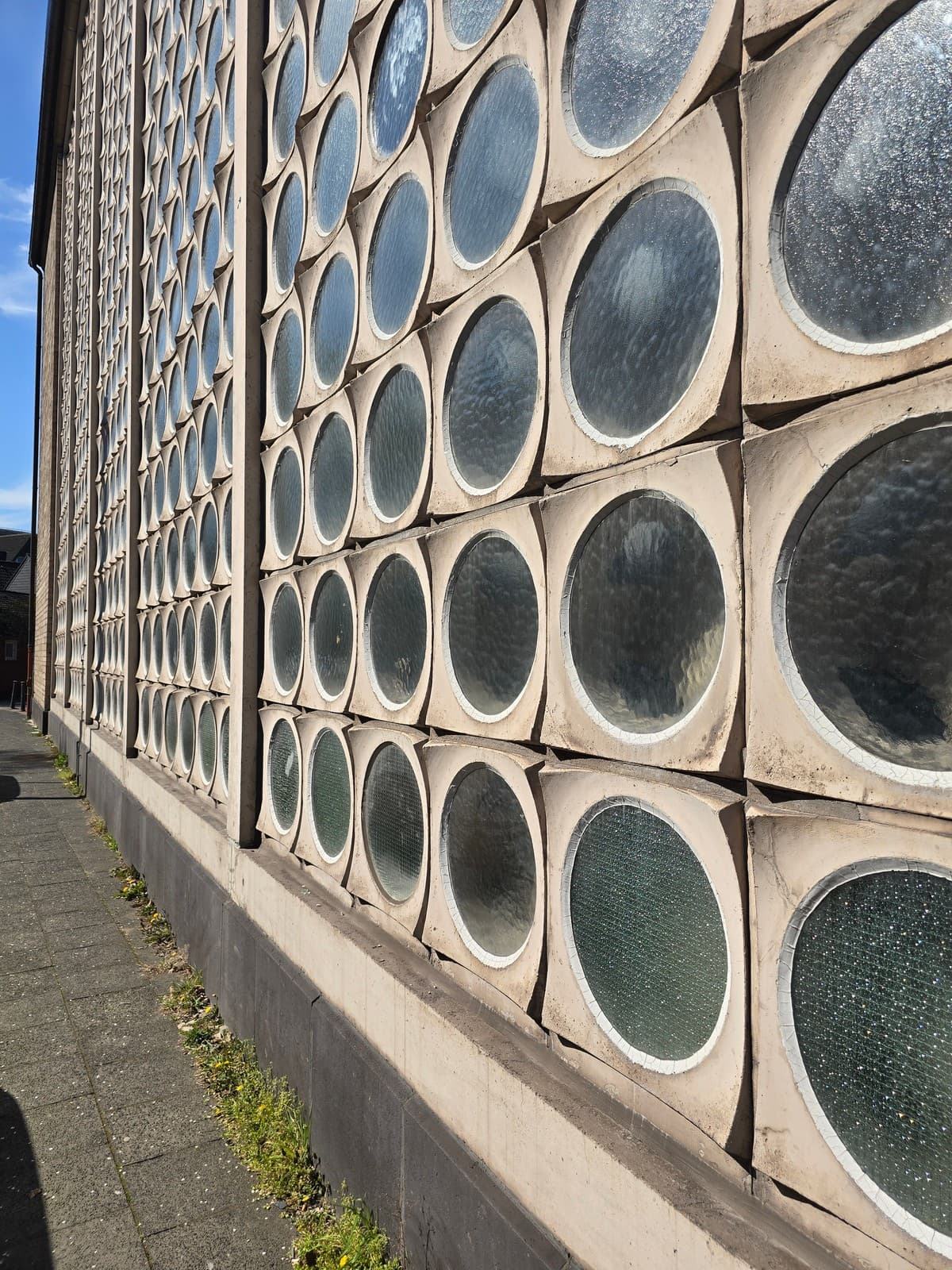

The Küppersmühle is considered to be the major attraction of the city, as it hosts the Museum of Contemporary Art, well known in the country and abroad. The museum is a converted complex of a former mill, that was built in 1908. During its rather short period of duty the mill has been upgraded several times. Among the most prominent upgrades was a set of concrete and steel silos used to store grain.

In the year 1972 the mill was closed, and was under threat to be demolished. However, the town residents petitioned the city authorities to save the building. The musem was opened in 1999.

After a long period of struggle the museum received another extension in 2021 - the eastern wing, allowing the museum to increase it's exhibition space by 2000 square meters.

Geographically the building is located at the end of the city channel, so any visitor can quickly get to the opposite side and take a couple of gorgeous photos.

The riverbank in this area also retained the industrial rails, along with some of the equipment.

The texture of the metal casing of the silos is just so beautiful. And look at that fine example of steel fachwerk.

Right by the museum a funny mock of a submarine was "docked". I didn't get a chance to look inside, but from a fragment of the dialog I happened to overhear I understood it was just another room to host a collection of photos.

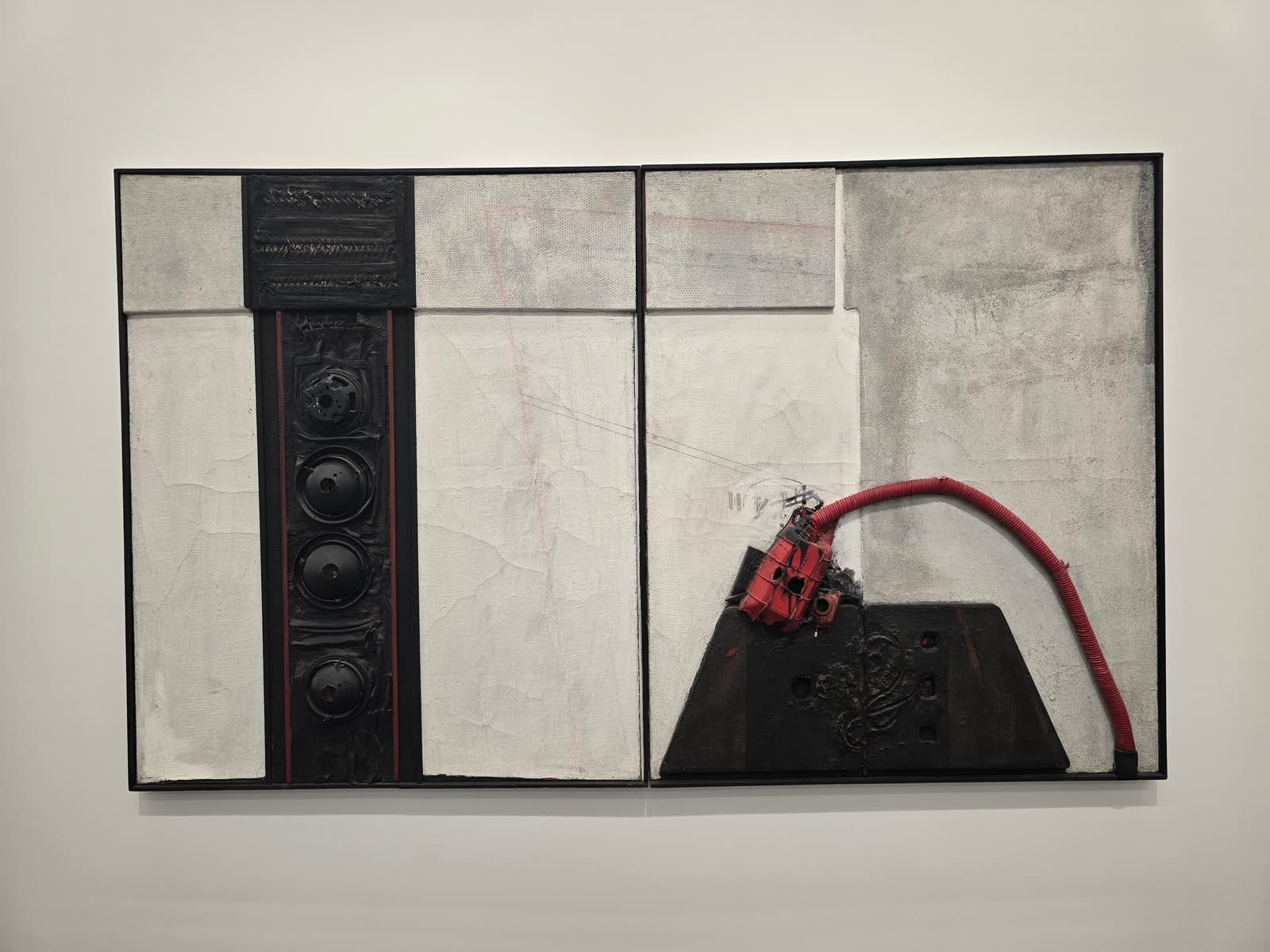

How gorgeous the exteriors of the building are, the interiors are the entire opposite of it. The architects buried all the brick textures and the industrial elements under a thick layer of white plaster and paint. No cranes, no equipment, no riveted beams or anything like that. Just. White. Cubicles.

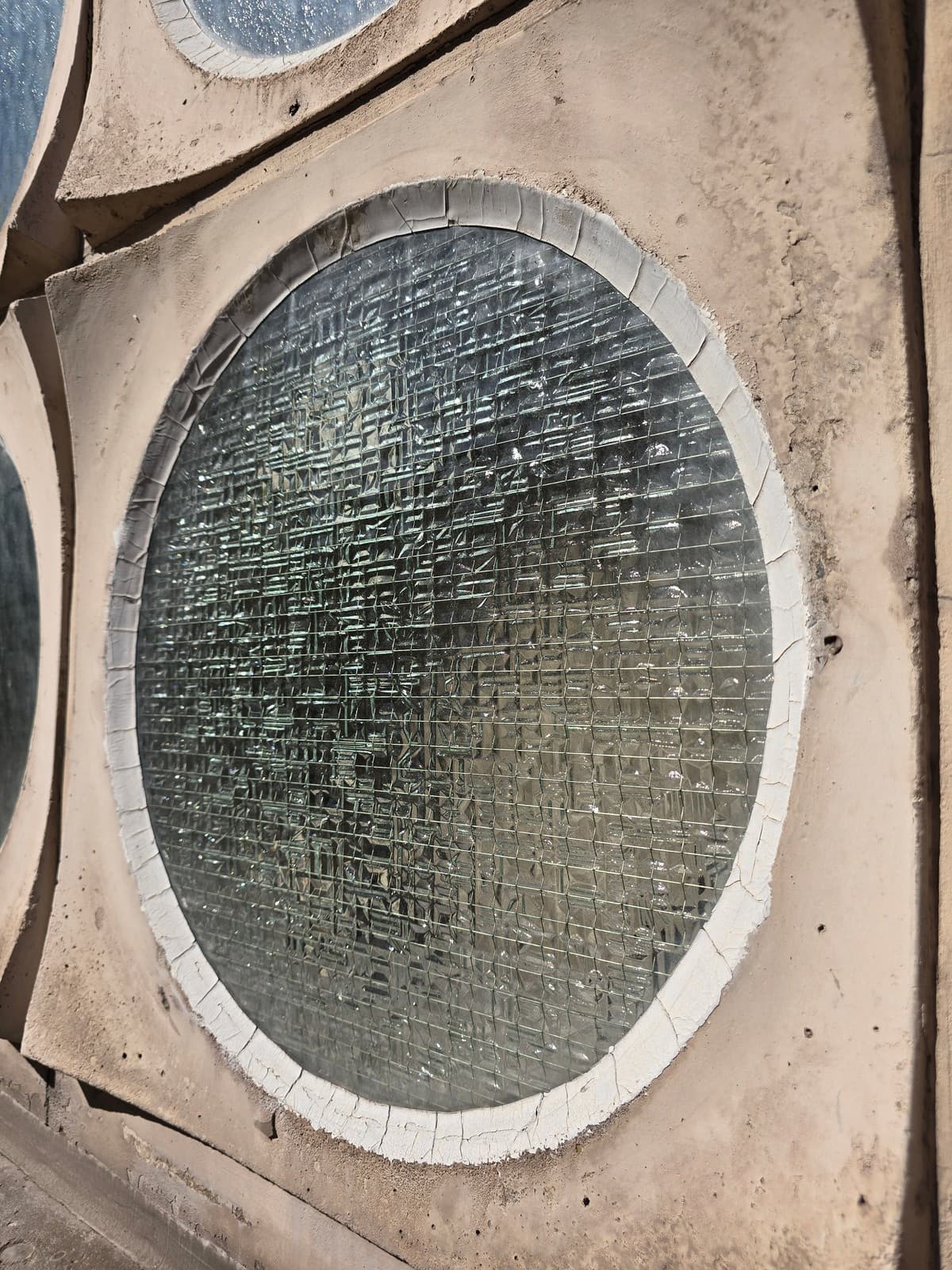

It was disappointing, to say the least. The only interesting room was the old silos, where you could feel the perspective and the sheer size of the place.

The cuts through the ~20cm thick silo walls gave the impression of might this place possessed once.

Another stunning part of the museum were two staircases, but ofcourse, these are two new additions, constructed after the conversion into a museum.

With the lines and proportions just so beautiful, the stairs made of concrete mixed with paint serve as a perfect example of what can be achieved even with simple raw materials. Come to the museum on a sunny midday, and you witness the geometric patterns created on the walls of the staircases by the sunlight going through the narrow and tall windows.

Honestly, I am not a big fan of contemporary art, so the exhibition didn't impress me much. I kinda liked the installation that reminded me of the companion cube from the Portal series.

The objects made of metal tubes and shards were kinda nice to discover.

There was an entire section dedicated to work of some author who used to paint caricatures that apparently mocked christianity and other auraamic religions. I found them kinda funny, but I don't think it's a good idea to post the photos here.

You should go and see for yourself, I'm not gonna spoil it for you.

On my way back to the parking lot I've decided to take a glimpse at the city center one last time. Duisburg was a beautiful city once, and the remants of it's beauty are still visible today.

If only the city authorities decided to tear down that ugly worn out shed running along the buildings, the area would look much better! Perhaps, one day it will happen.

Duisburg may not seem like much from the first glance, but it surely has a lot to uncover, should you dare to dig a little bit deeper and wish to see more.

The eerily quiet inner harbor and the empty docks of the Ruhrort induce the feeling of despair and desolation. Being deprived from it's historical role of a major industrial and transportation hub, Duisburg is trying to reinvent itself as a cultural center.

It would be interesing to see what good will come out of it!

# Links

- Meiderich ist nicht mehr, Duisburg brennt noch

- Die Niederrheinische Gesellschaft informiert.

- Some of the best pictures of pre ww2 Duisburg that i could find.

- Германия | Дуйсбург (Duisburg): Приятный центр неблагополучного города

- Земельный архив в Дуйсбурге, Германия

- Das Rathausgebaeude

- Liebfrauenkirche

- Karmelkirche

- Burgplatz (Duisburg)

- Salvatorkirche (Duisburg)