Autumn Underground 🍁: Goslar & Rammelsberg

My son and I got a chance to spend a weekend together. Initially, I planned to visit Poznan, as the city lingered in my to-visit list for quite a while. However, after doing brief Google Maps research, I realized it wouldn't probably be that interesting for the kid, so after a short brainstorming session with ChatGPT, the choice fell on Goslar.

It was a good option: only 2.5 hours away from Berlin, and the region of Harz remained largely unexplored by us.

Right before departure, I booked a room in a budget hotel outside of town, which was okay since we travelled by car. The main goal was to visit the Mines of Remmelsberg, and the hotel was just around the corner.

Even though the hotel's rooms were quite simple, the exterior reminded me of an open-air museum: we could find different kinds of historical artifacts attached to the facades, leaning against the walls, or scattered around the area.

The most remarkable items were, in our opinion, quite well preserved Singer sewing machine, the ironing device (apparently) and another device we couldn't figure out the purpose of.

Only later, I googled it was actually a carding machine. ChatGPT couldn't figure that out, but an old-school Google search by an image could. This was the only machine my kid really liked, primarily because the rest of them were hopelessly jammed on purpose, apparently to avoid risks of flattened or torn away children's fingers.

The dusk was slowly getting upon us, but we decided to take a 20-minute walk to Goslar nevertheless. It was a nice exercise after a 3-hour drive, as my legs and back begged for a warmup. I briefly considered taking a ride on a bus, but the bus stop near the hotel looked really deserted, so I discarded the idea. I wondered if a bus was seen there at least once an hour.

Timbered plastered houses on the outskirts promised the city would be an amazing experience.

Some of the houses looked like haunted manors in the dark, and my son looked excited. He couldn't stop chatting about vampires, witches and ghost-occupied rooms. We spent the entire walk discussing how the very first vampire came to be.

The very first remarkable building we noticed was a strange structure next to the parking lot, which looked like a chapel and seemed to be completely out of place.

Inside there was a room full of decorative parts that clearly belonged to a building once.

In front of the "chapel" there were two massive stone heads laying on the side.

Brief research revealed that it wasn't a chapel at all, but rather an entrance, or Die Vorhalle. An entrance to what? Believe it or not, but the parking lot behind the lobby occupied the space where the Cathedral of Goslar once proudly stood, and the splinters seen inside the porch are all that is left of the church.

The church of St. Simon and Judas was constructed by the Emperor Henry the 3rd around 1050. It was an impressive 3-naive basilica, once the biggest one in North Germany. However, after Goslar ceased to be a residence of the Emperors, the Cathedral lost its significance. The building wasn't bombed or perished in a fire: rather, it slowly decayed over the centuries, and around 1819 was sold to a private company and eventually dismantled.

This is how nations loose their heritage - through lack of funding and purpose.

Research was conducted in the present days, and the remnants of the foundations were discovered just below the ground. A pending project is rumoured to propose replacing the parking lot with a recreational area that would allow opening the foundation walls for display.

The city government has funded the development of the application that shows a virtual reconstruction of the cathedral.

We have visited the place next day and took a few photos in daylight.

The early November evening was quickly getting darker. We rushed to the main square to capture the view of the old town before it completely plunged into the night. The streets were surprisingly poorly lit, and my camera wasn't particularly good enough under such conditions. Next time I'll bring my iPhone, and we will see if it makes any difference.

The fountain of the market square was the only beacon of light. I could make out the details, but quite poorly.

Since we didn't have a proper lunch, we stopped by a restaurant serving German cuisine. The restaurant occupied an old timbered house and looked really promising. I took a few shots and couldn't decide from which angle the building looked the best, so I kept all of them.

The interiors didn't disappoint.

Brittle and weathered yet forceful wooden beams made a solid impression and didn't bear any signs of being newly fabricated.

Right by the restaurant, there was an old mill occupied by the museum of tin figures. After I did some brief research, my kid and I agreed that it would be the place we were going to visit tomorrow afternoon.

Hey, that dragon misses a tile on its armor, certainly, there used to be a gemstone before 🐉

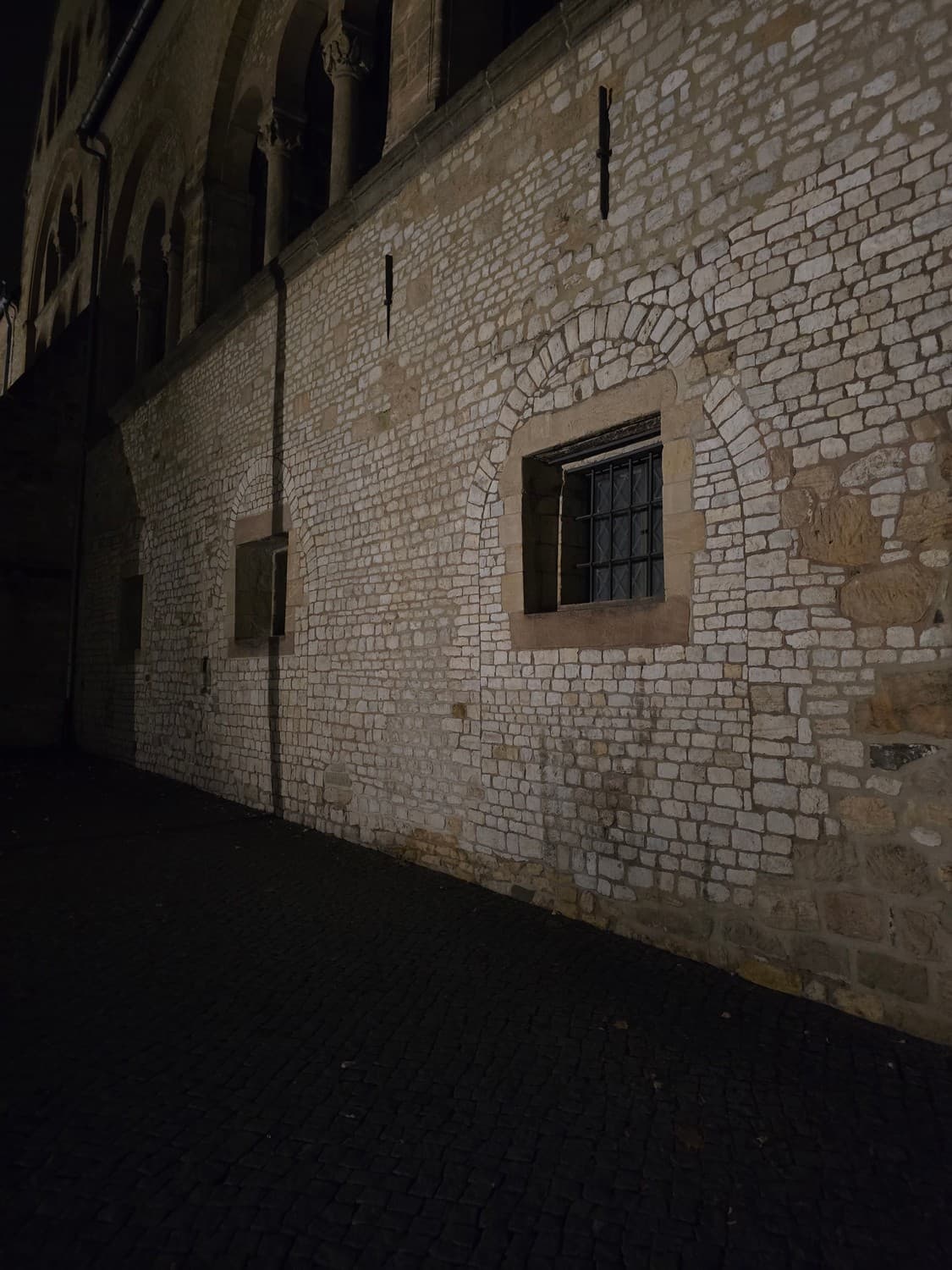

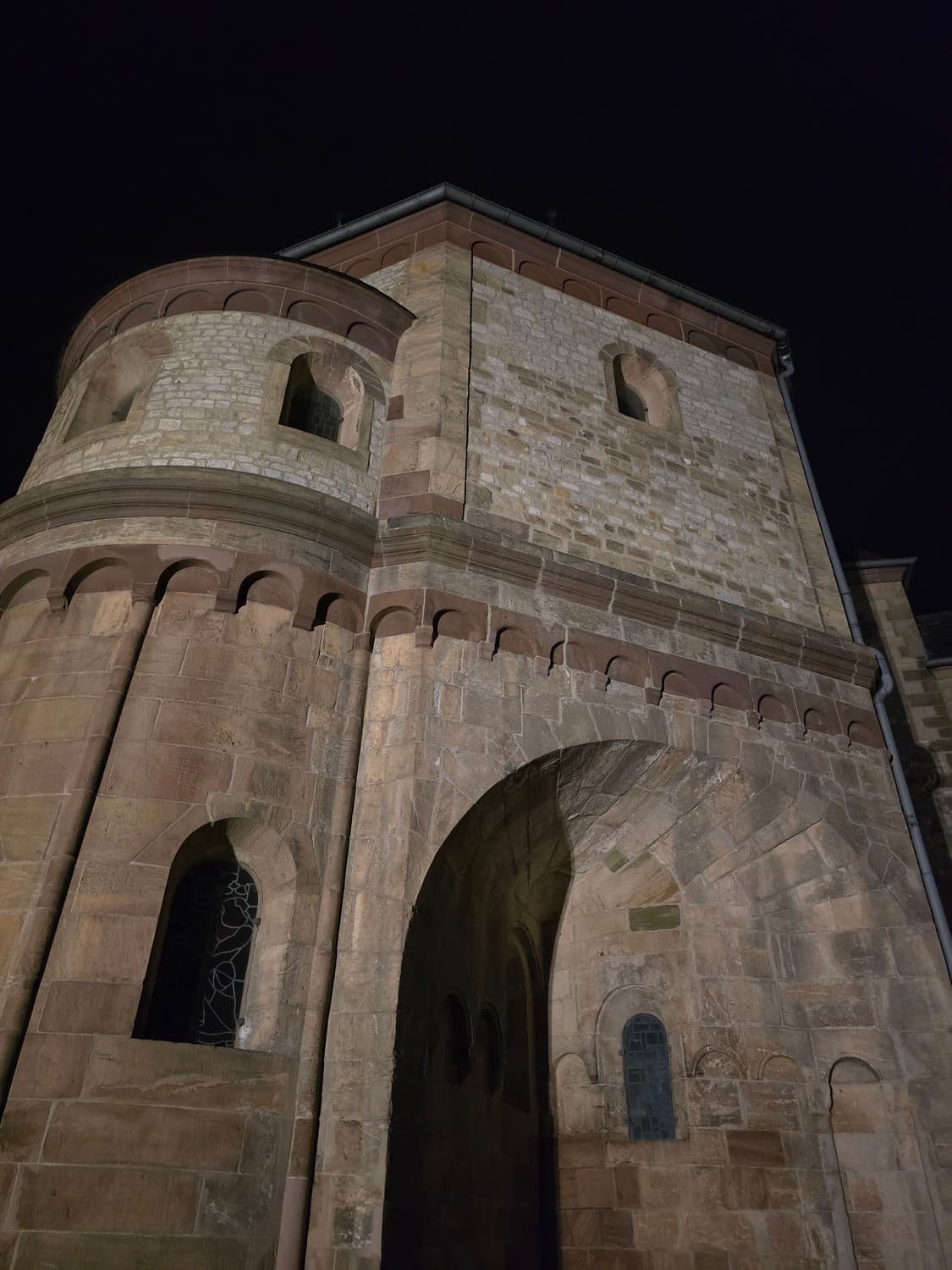

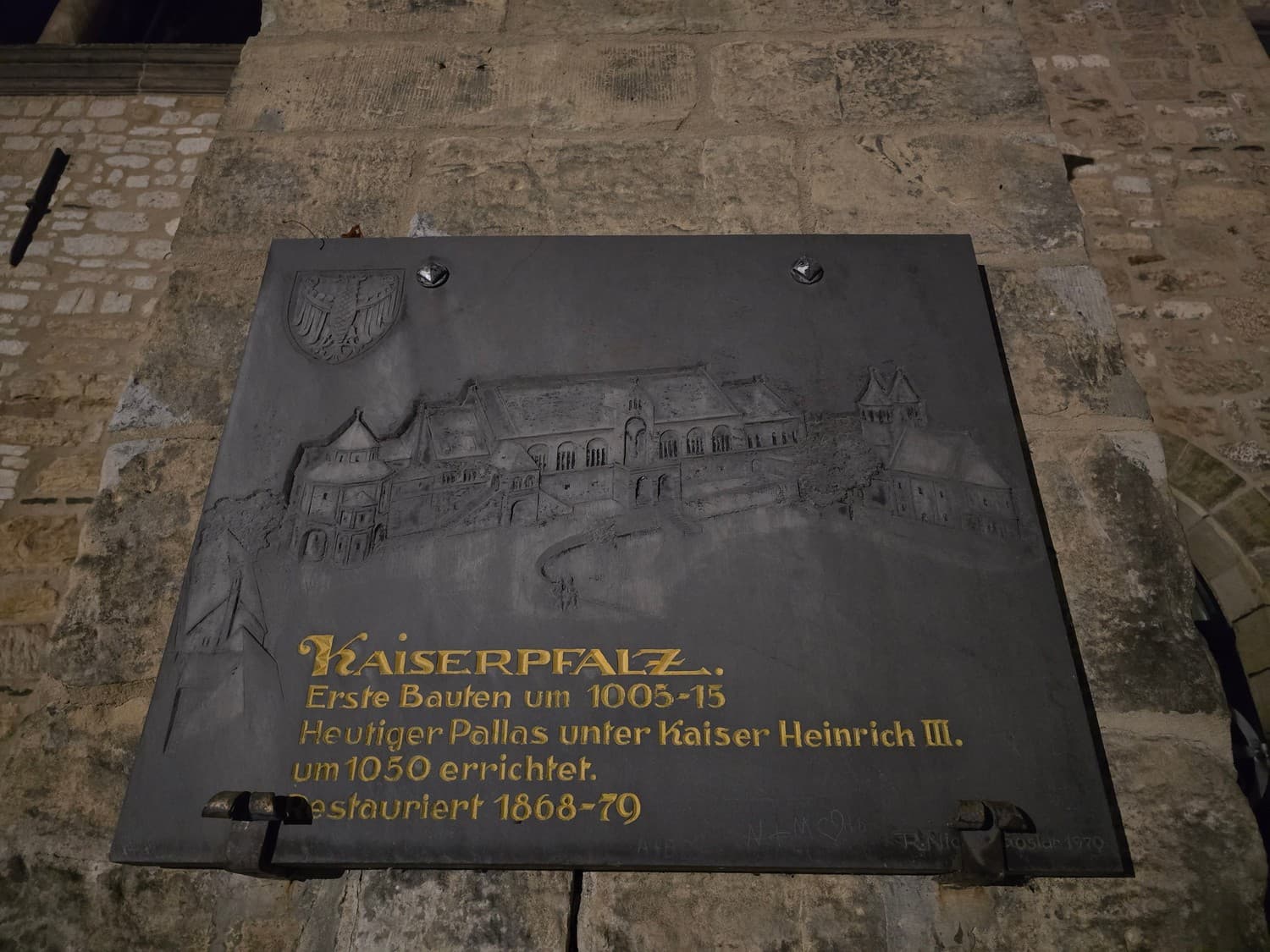

On the way back to the hotel, we took a detour to briefly see the Imperial Palace - Die Kaiserpfalz, which nowadays serves as the main tourist attraction.

The Palace was constructed at roughly the same time as the now-lost St. Simon and Judas Church, and in fact used to form a single ensemble. This is especially noticeable in the architectural styles of the palace and the cathedral's vestige. They look very similar, giving the same Romanesque vibe, being constructed of the same stone and shade, and having similarly styled arched windows and doorways.

The interiors are said to be quite remarkable, displaying different paintings and valuable artifacts. Die Kaiserpfalz is a "must-see" place for every tourist visiting the city. However, it was already too late, and we obviously couldn't get in. I promised myself to fill this gap the next time I am in Goslar.

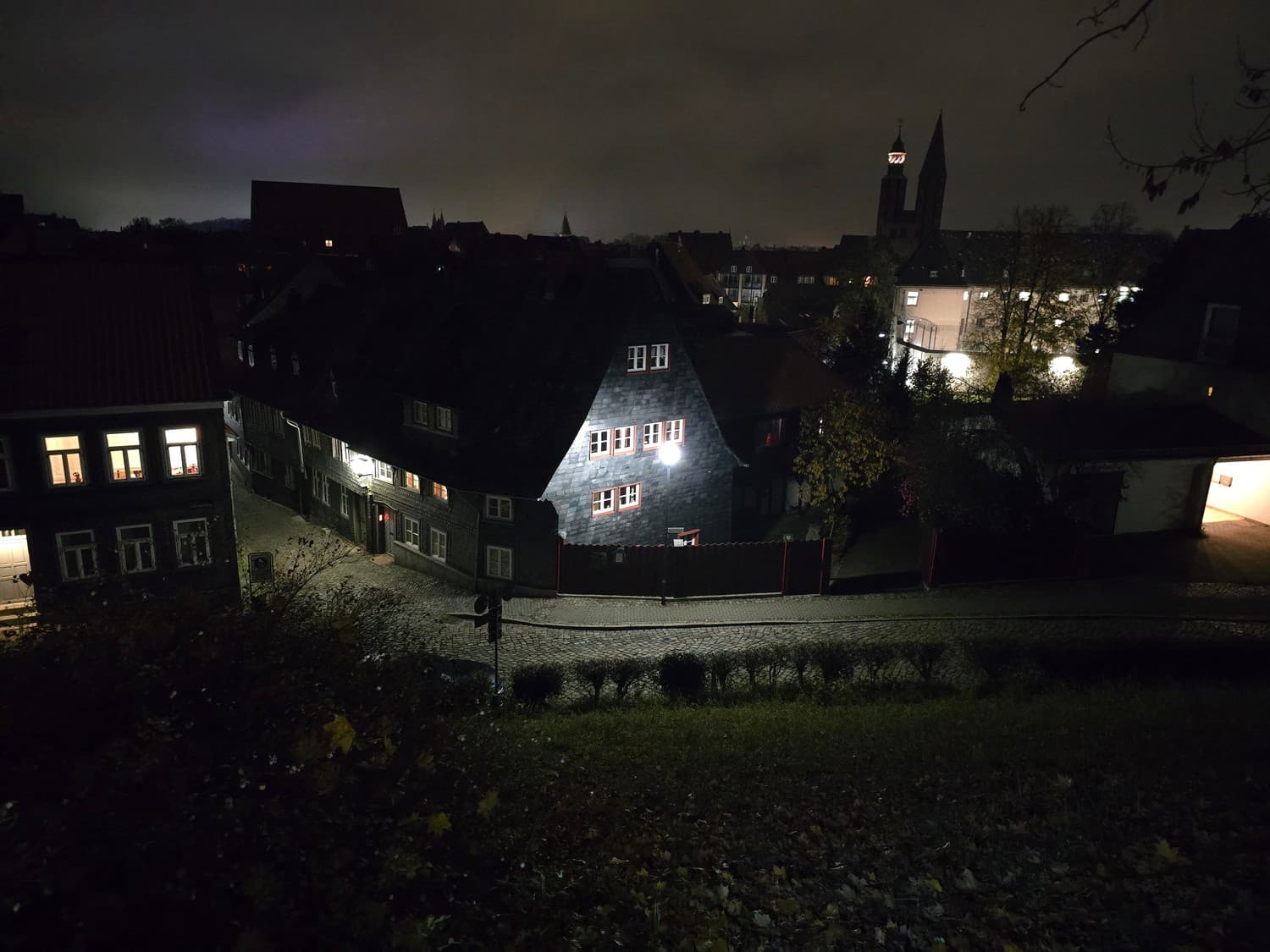

All tourist guides strongly advise going uphill behind the palace to see the iconic panoramic view of the town.

We walked the way back in silence, each occupied with our own thoughts.

Early in the morning, the weather turned out not exactly what I was hoping for. Low-hanging clouds mysteriously concealed the mountains of Harz, and the light rain made the cobblestone road leading to the mines, our primary objective of the day, darker and a bit glossier.

On the other side of the road stood a peculiar hexagonal building with a sealed entrance. I couldn't find out what it used to be, and there was surprisingly no information on the information stand next to it. Judging by the look of it, it could have been a warehouse.

We left the car in the guest parking near the complex, and for a brief period of time, we couldn't figure out where the entrance was. After asking around, we were given pointers to head 150 meters back down the road and look for a 3-arch main gate.

At the beginning, I thought the entire inner courtyard was most likely used to be occupied by trucks and different kinds of carriages; otherwise, I couldn't really explain the need for such a vast area, which was big enough to host parades. However, the architectural style of the complex reminded me of something, and my suspicions were later validated. The guys who built this part really liked their projects massive and visually overwhelming.

An entrance to the right led to a spacious lobby. The stairs were apparently part of the design and also to adapt the building to the uphill landscape.

The lobby was separated from the men's dry area by a gateway with 3 doors. I couldn't help noticing that every gate always had three doors: the outer gateway, then the one with the staircase, and now the one with an epic painting above. The painting was dramatic, as always.

Mining operations on the mountain Rammelsberg were first officially mentioned in 968, and the Rammelsberger mine, which was being constantly modernized over time, was only closed in 1988 after depletion of its deposits. Since it has such a long history and has been witnessing technological advancements in mining for about 1000 years, the site very well deserves the right to become a part of the UNESCO heritage.

After going through the door below the mural, we entered another vast hall where miners used to change after the shift. They hung their clothes above the ceiling using metal ropes and then went to take a shower. The clothes would be dry by the next morning, thanks to the air circulating through the wide windows above.

My kid asked if we would have to take a shower too. Huh, he doesn't like washing, what can I do? 😅

But jokes aside, the Rammelsberg mine isn't a salt mine, which is usually relatively safe. Here, people used to mine copper, zinc, silver, gold, and a bunch of heavy metals, so it would be unwise to lick or touch the walls of the mine adit. It isn't a good idea either to dress in all white for the journey :)

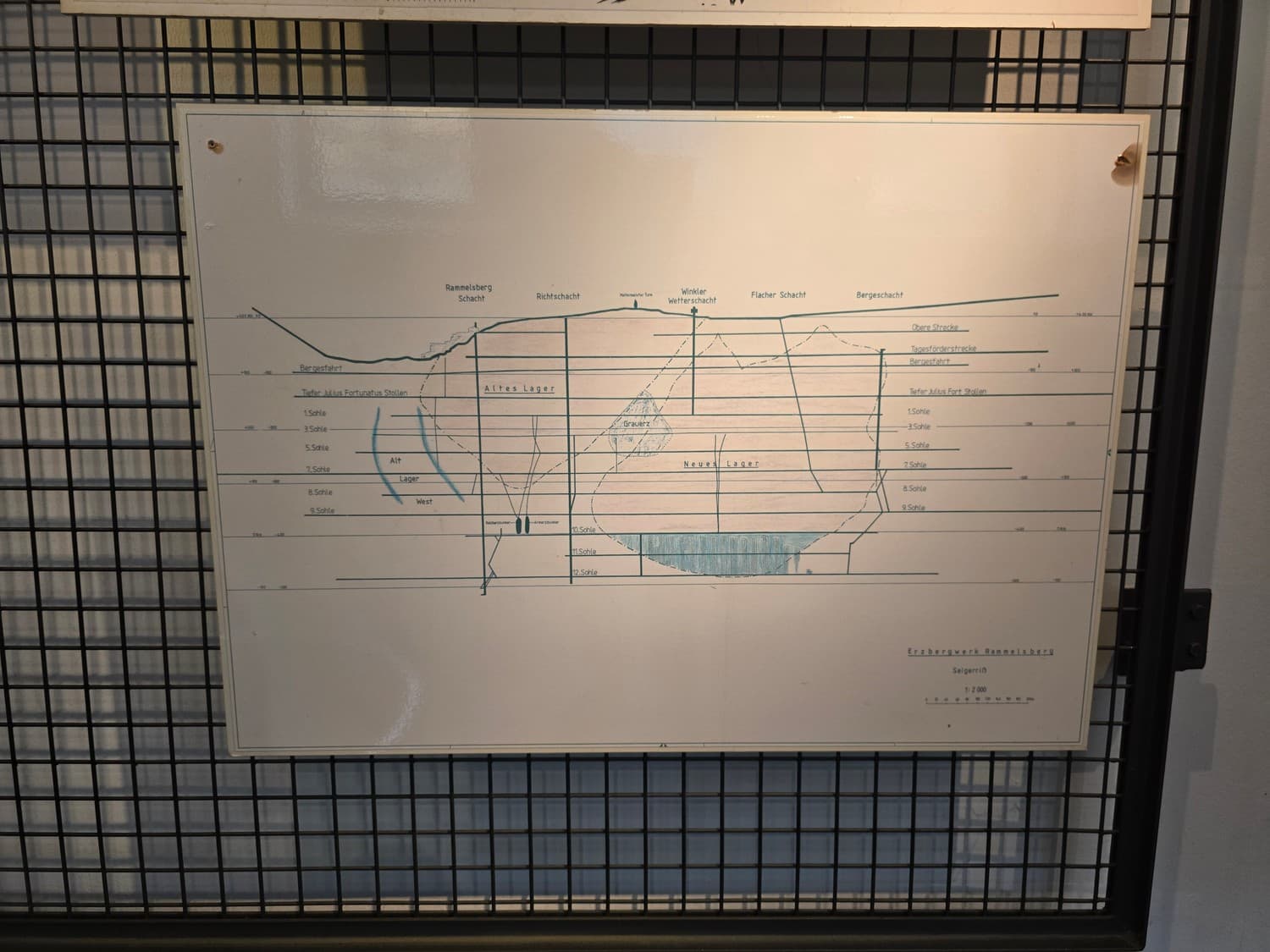

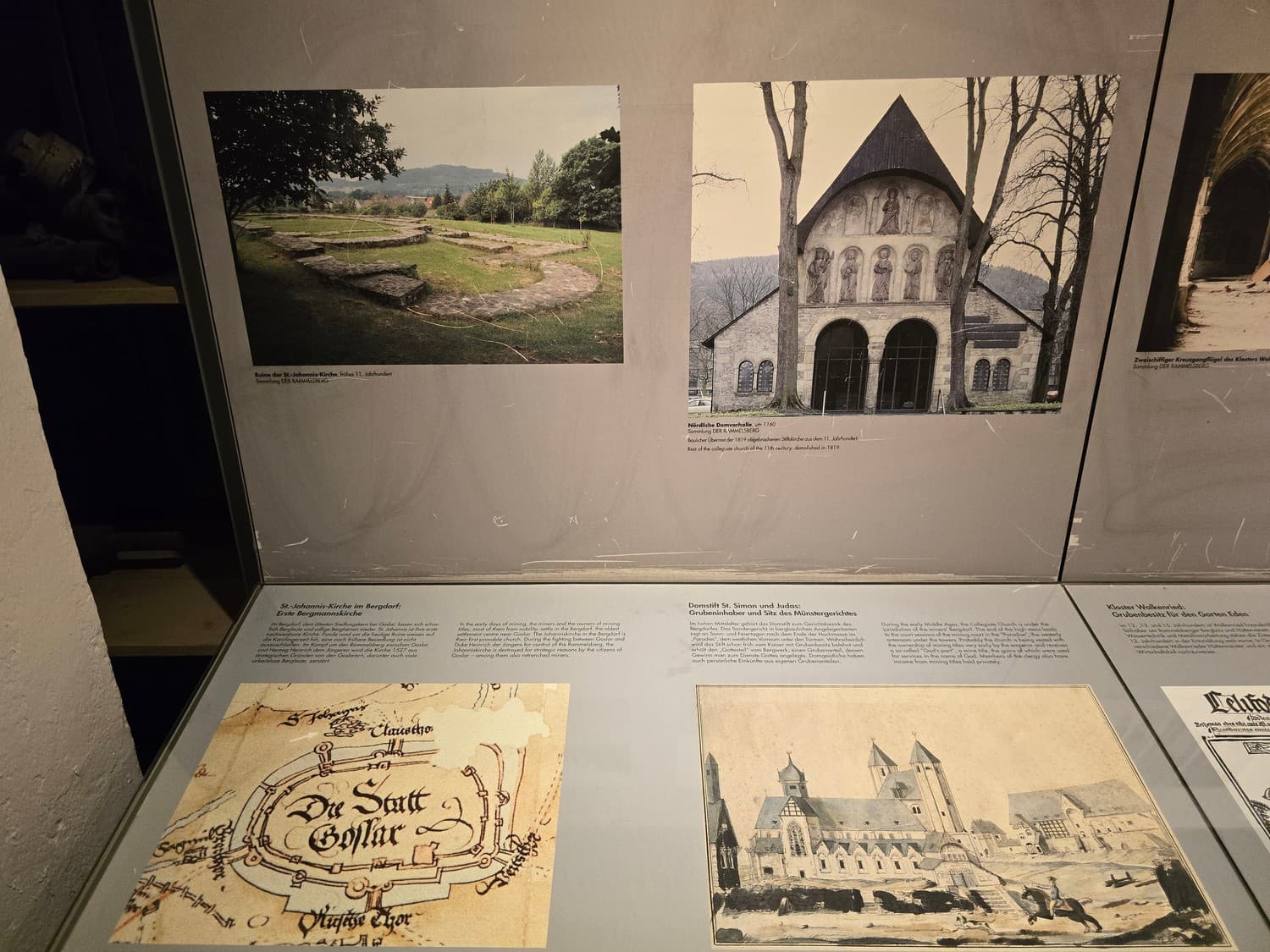

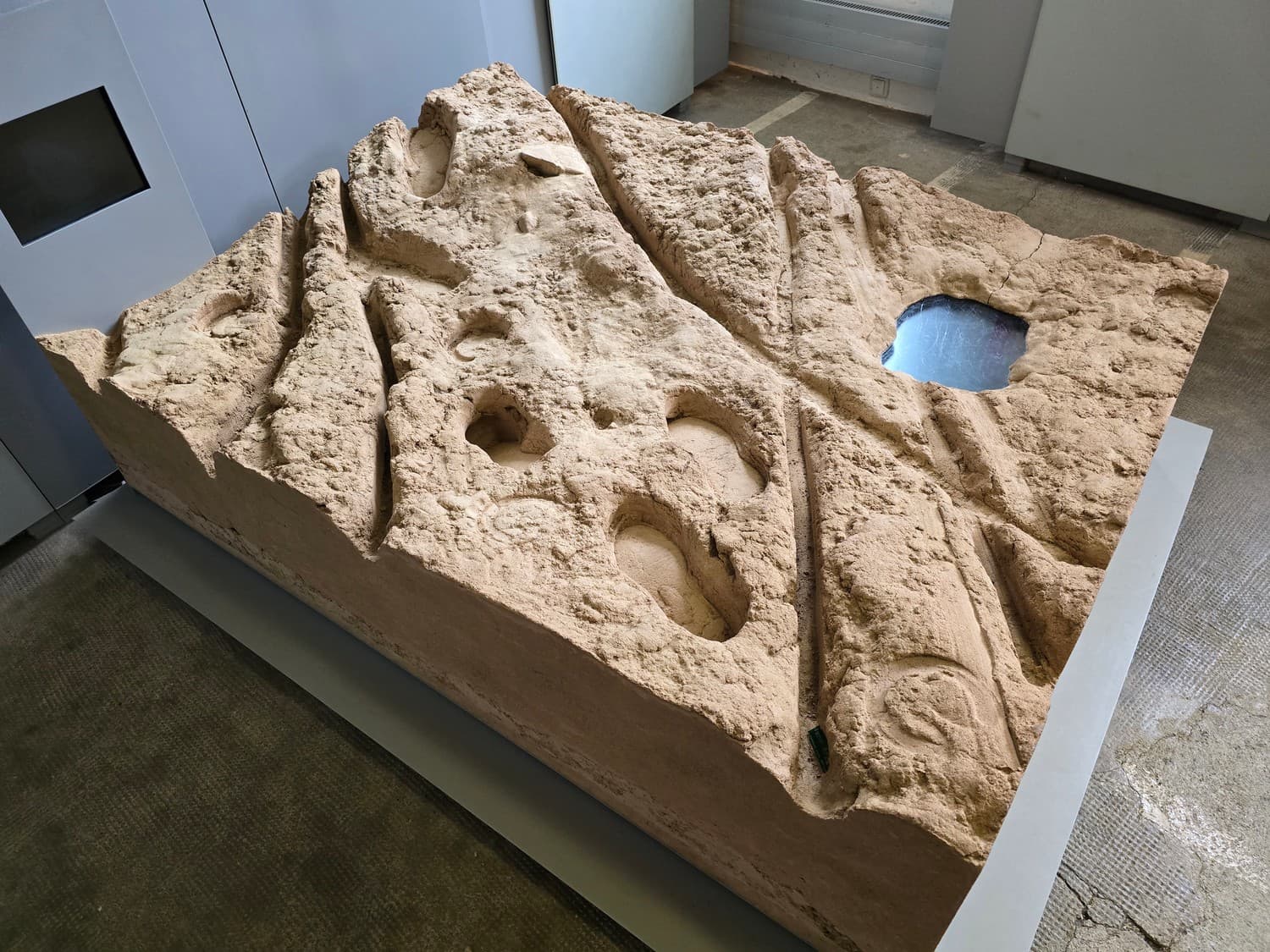

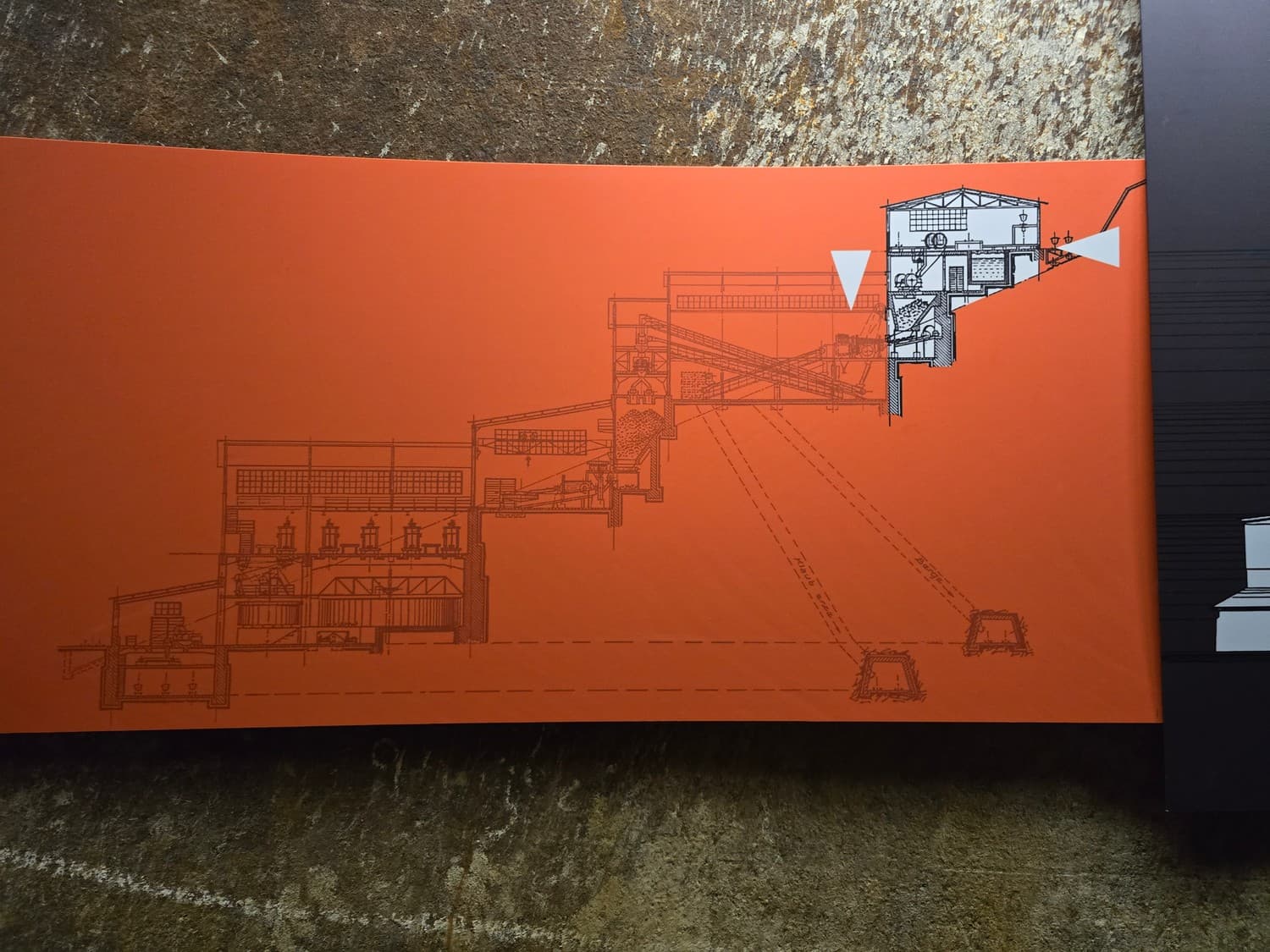

Since we came a bit earlier, we had about 20 minutes before the start of the tour. We watched a short documentary about a typical day of a miner, and also studied the model of the mine. The complex rests on the slope of a mountain, with its adits going up to 500m deep. The model depicts the state from 1932, so it doesn't have the ore refinery (the building most recognizable visually today), since it was built later.

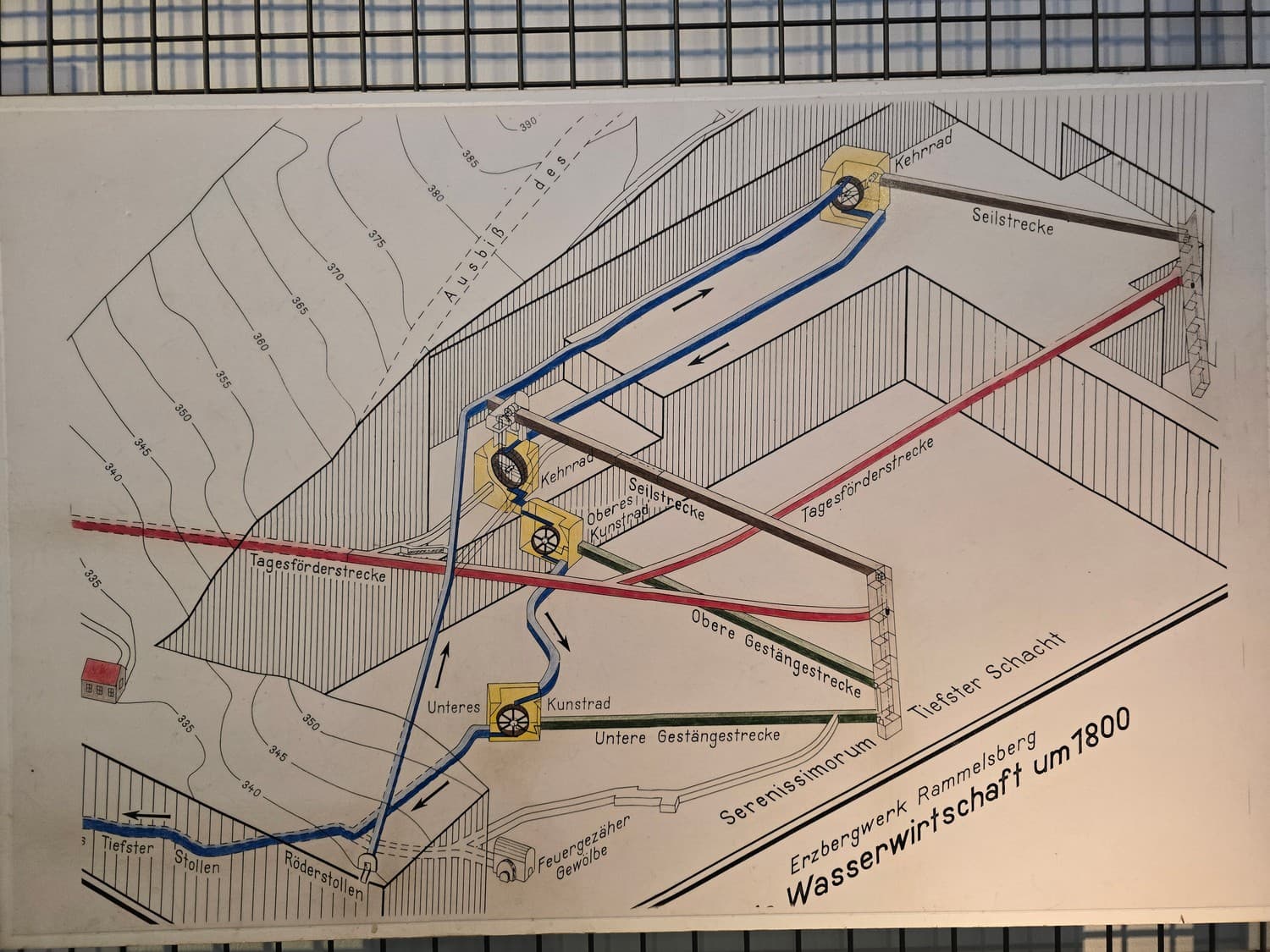

There were also a couple of interesting diagrams showing the shape of the deposit layout inside the mountain, and the way the water energy pipeline from 1800 functioned before the mine was electrified. I bet all these halls where the wheels used to be still exist today, and perhaps even available for sightseeing with another dedicated tour.

Upon taking a tour at Rammelsberg, a visitor has two options: take a walking tour to the mine, where they are given a more thorough lecture on mining equipment and the history of its evolution. The other option (which we took) was riding a mountain train. It was supposed to be much more amusing for kids.

It was, however, a disappointment to a certain extent that the carts of the train were completely sealed. Well, by far nothing beats the fun of riding an open train taking you to the bottom of a salt-deposited mine, which we experienced in Salzburg.

Each cart of the Rammelsberger mine was capable of carrying up to 10 miners, and if you are claustrophobic, I would strongly advise against the trip.

The entrance to the mine wasn't as pompous as I anticipated, either: just a comparatively humble passage letting the train through.

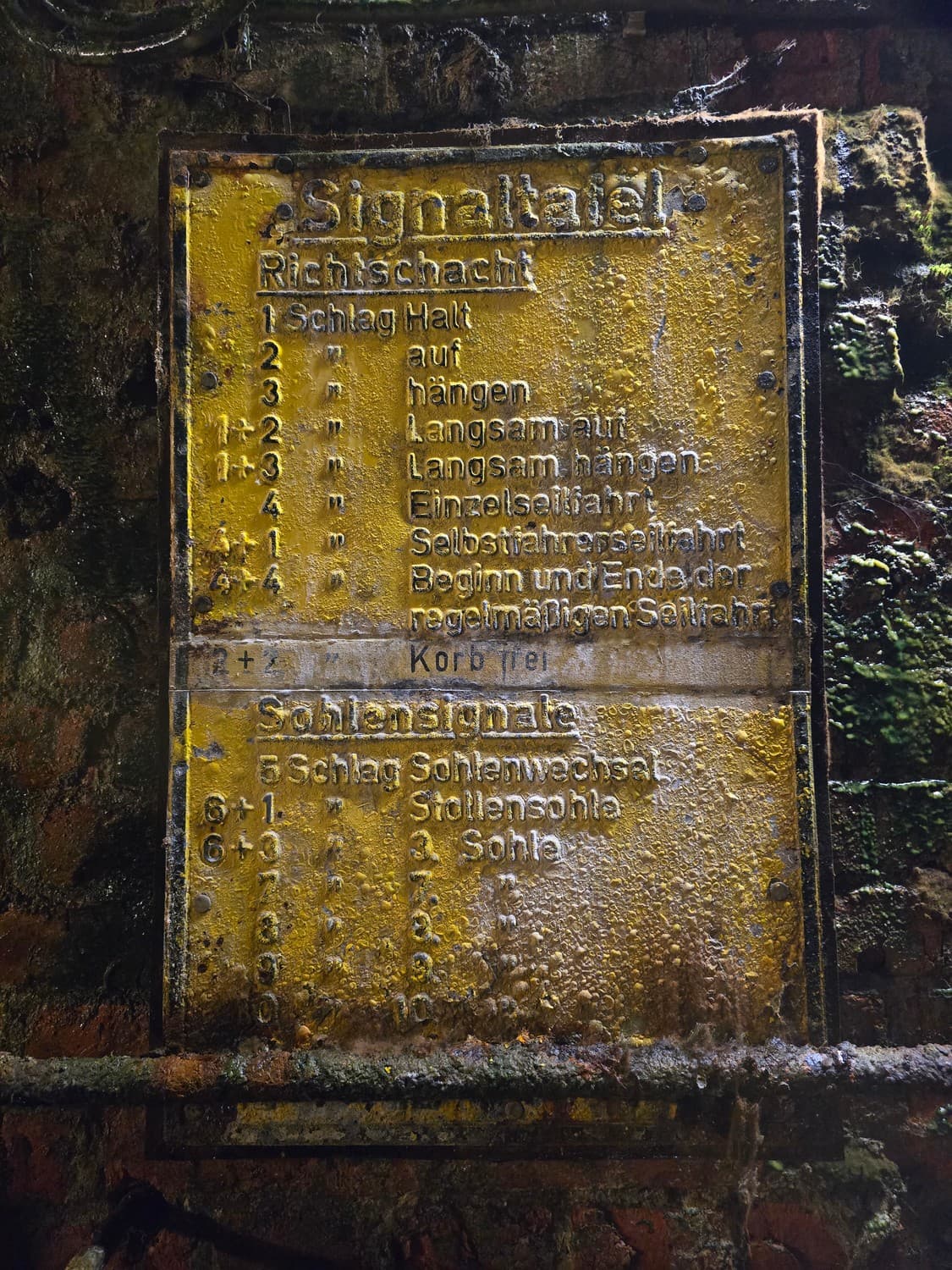

The ride on a clunky train swinging sideways in almost complete darkness took about 10 minutes, until we finally stopped by a rusty metal gate, beyond which the visitors were not allowed. Apparently, this is where the horizon ended, and a vertical shaft that descended to the bottom began.

The walls and the vaulted ceiling here were covered with green slime (which turned to be moss and fungus, feeling like home there), rust, and black-white efflorescence of heavy metals (again, refrain from licking the walls, even if it's hard to resist the temptation).

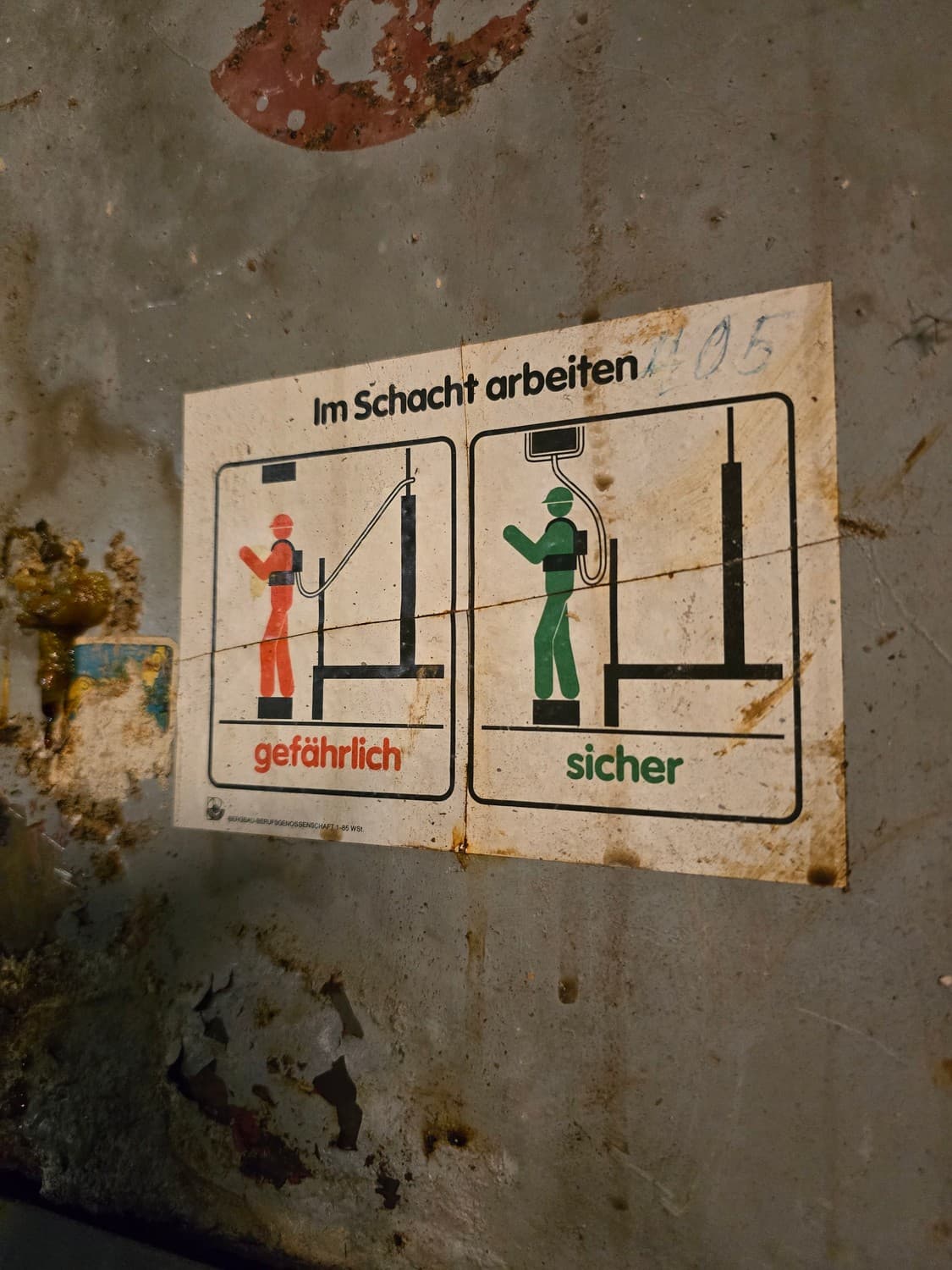

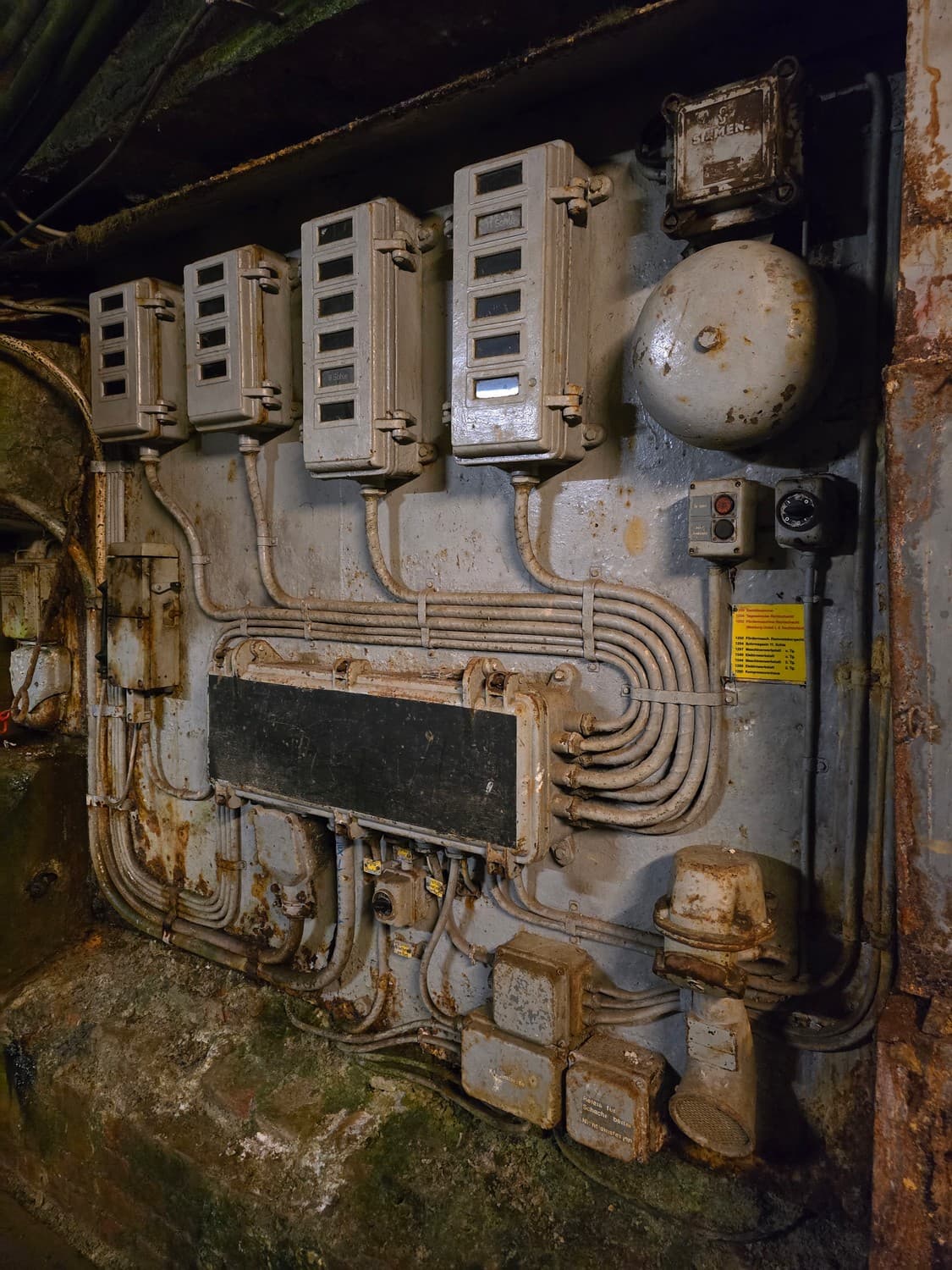

I took a couple of close-ups of the equipment on the walls. What a fine piece of props they would have made if 3D-scanned!

The exhibition presents a typical breakfast alcove where workers could rest. Next to it, there were also a telephone and a water sink at their disposal. There was no risk of being exposed to underground pockets of poisonous gas in Rammelsberg, so there was no need to keep a canary in a cage.

During this short tour, the evolution of mining operations was presented. Starting from basic carts that require the ore to be put in manually using shovels, to more advanced dump and overhead carts.

Three ways of cutting into rock were also demonstrated: a hand drill that could be used to cut the rock in any direction (yet the hand joints of a miner would be wasted to heck), an engine-powered horizontal drilling machine (a very loud one, on regular tires instead of typical rails), and, of course, dynamite!

It is important to understand that all the equipment in the mine is more than 40 years old. Since then, the technologies have advanced a lot. For instance, nowadays, an operator can remotely control a mining harvester from an office chair.

A human being can adapt to a variety of harsh conditions, but I can certainly tell that mining is a hard duty. It is cold, wet, dense, and dark in the mine, so I believe this job isn't for everyone.

After the tour, we were free to explore other parts of the facility.

There was a good exhibition with a generous variety of showpieces. Normally, I would have stopped by to read most of the labels, but I couldn't tolerate the stench of metal, lubricant, and old wood that permeated the entire workshop. It was so unbearable (even by my levels of tolerance) that it made me dizzy and really uncomfortable, so I limited myself to brief browsing. The kid seemed okay with it, though.

Here are some of the many showpieces presented there.

A church spire was cut into segments and scattered around the exposition. It was only there because it was an example of what could be produced using raw materials mined here. If you ever wanted to pretend crawling the rooftop of a church, here is your chance.

Another spire is used to decorate a staircase leading to the level below.

The railway depot gave us vibes of the "Stalker: The Shadows of Chernobyl" game.

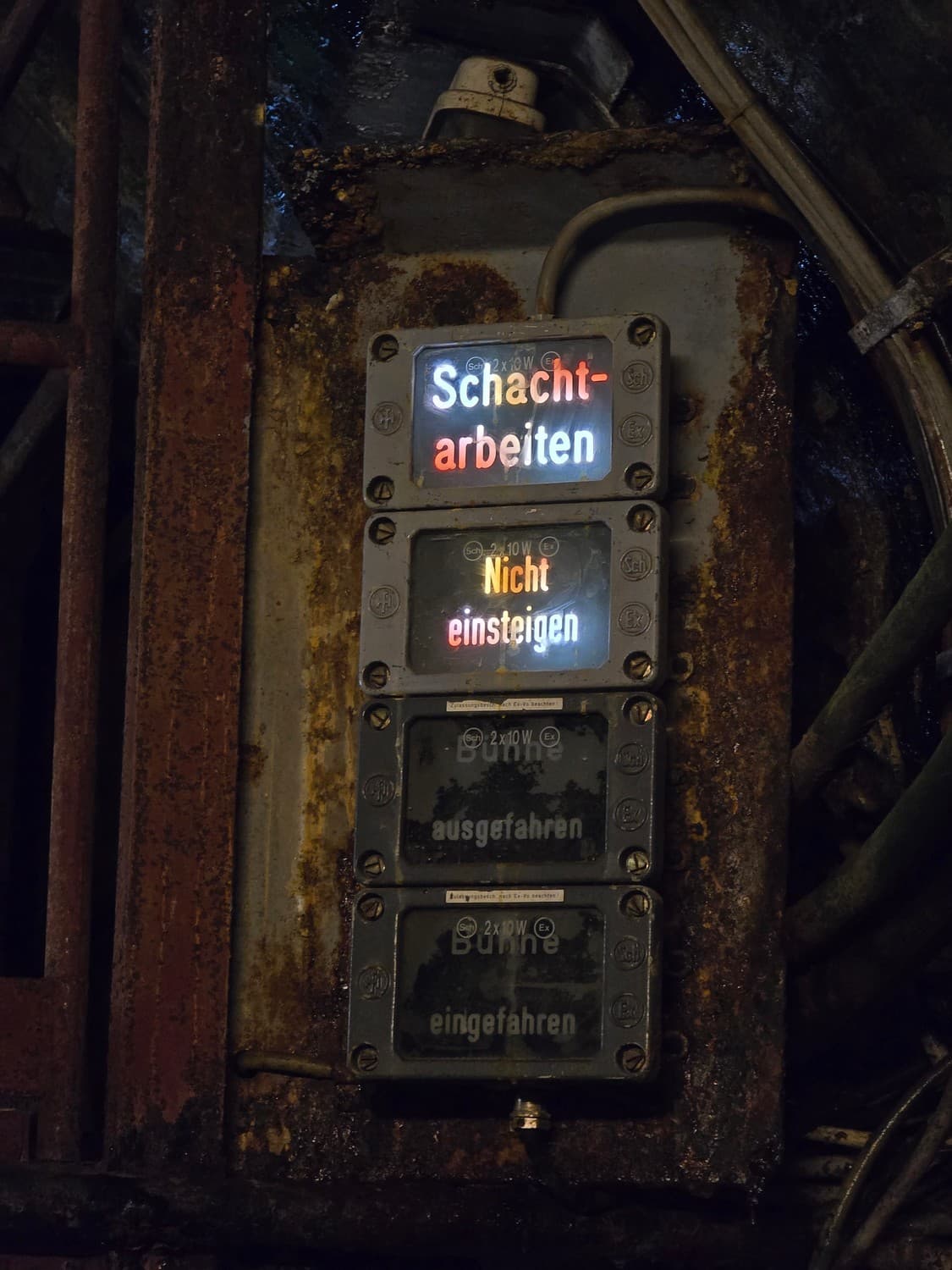

The info screens roared in eerie silence, and there was nobody around, just the echo of our footsteps.

The desolation of the railroad equipment that most likely would never move again gave us chills, so we hurried up to the exit.

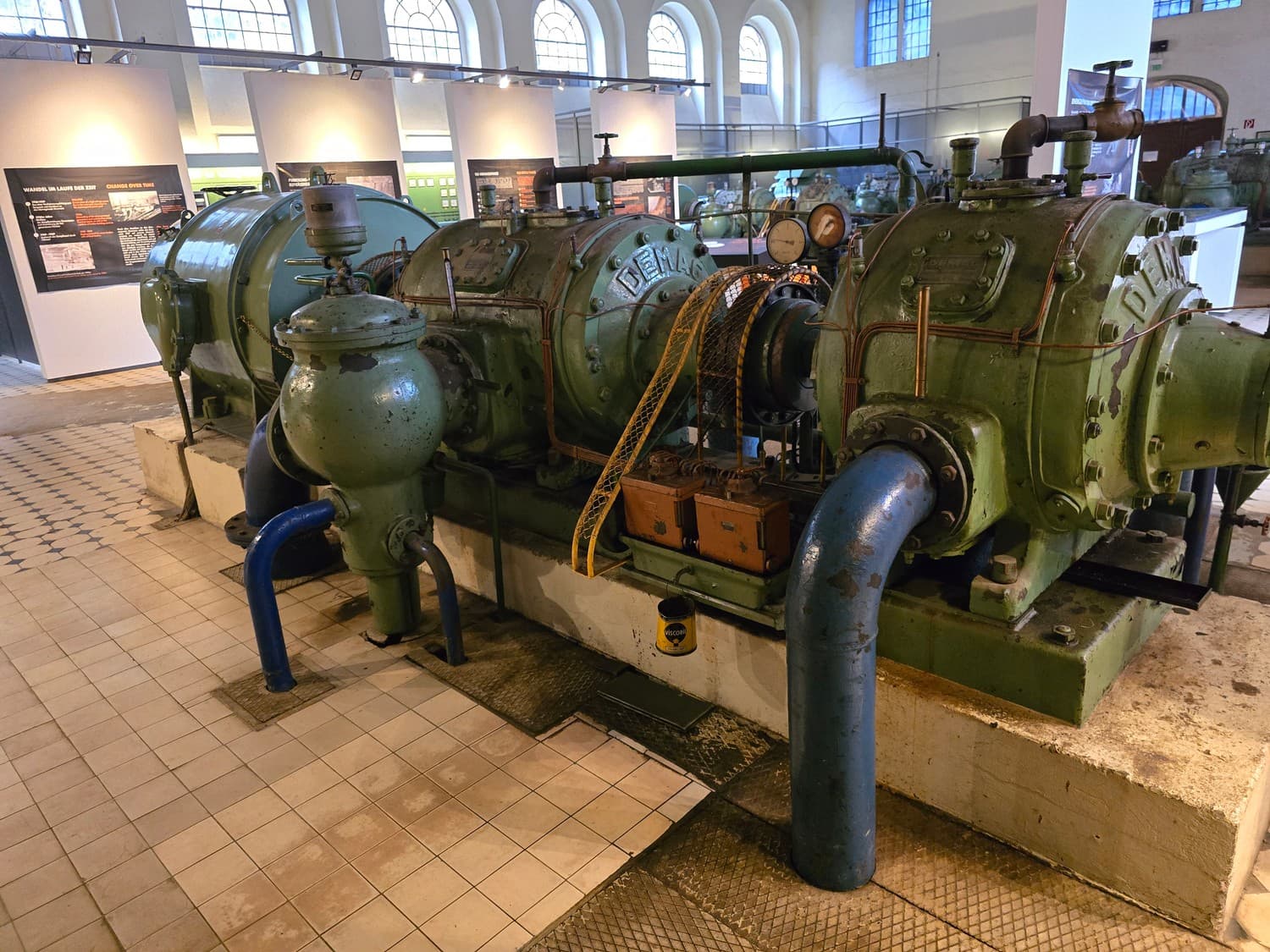

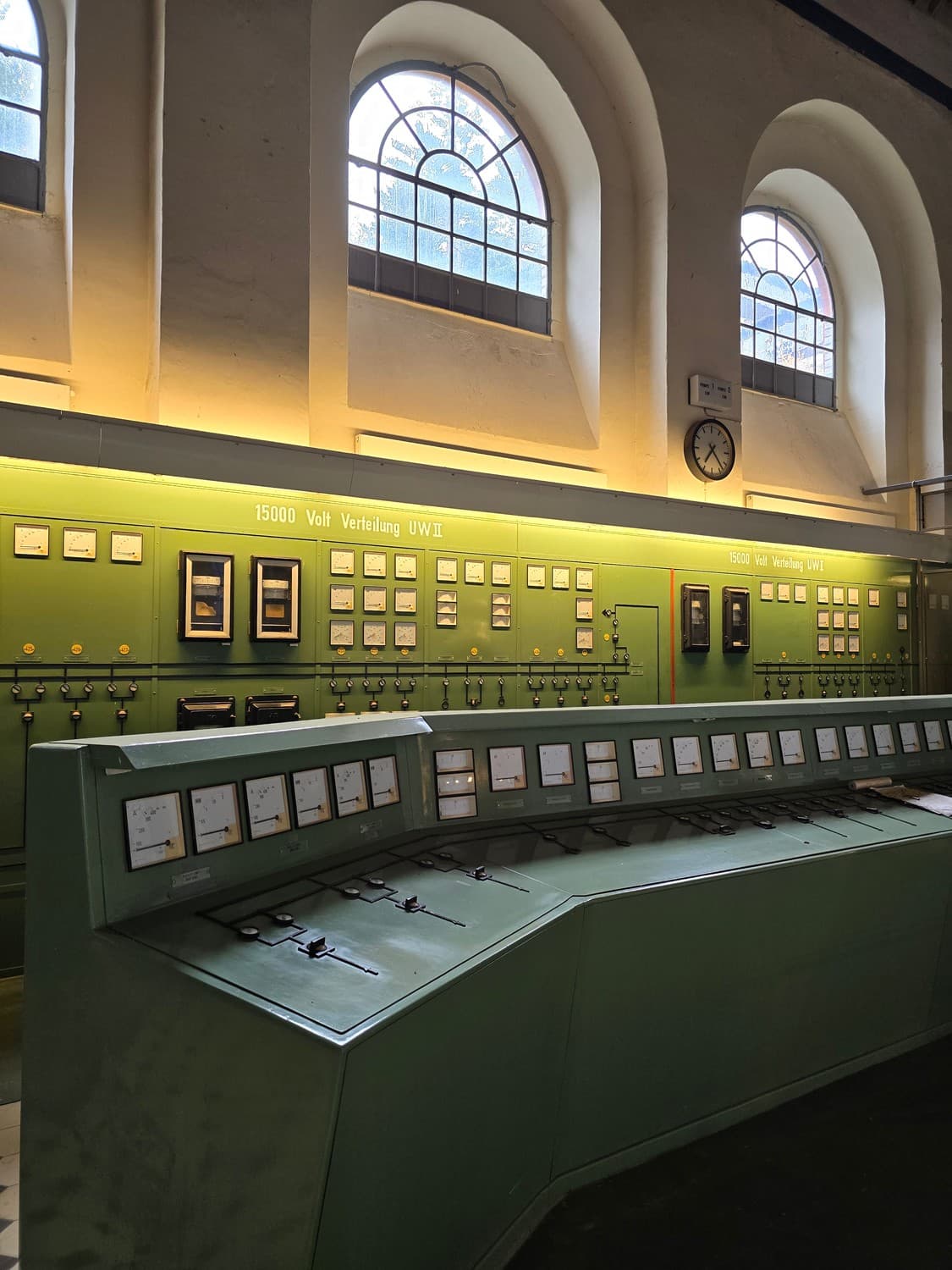

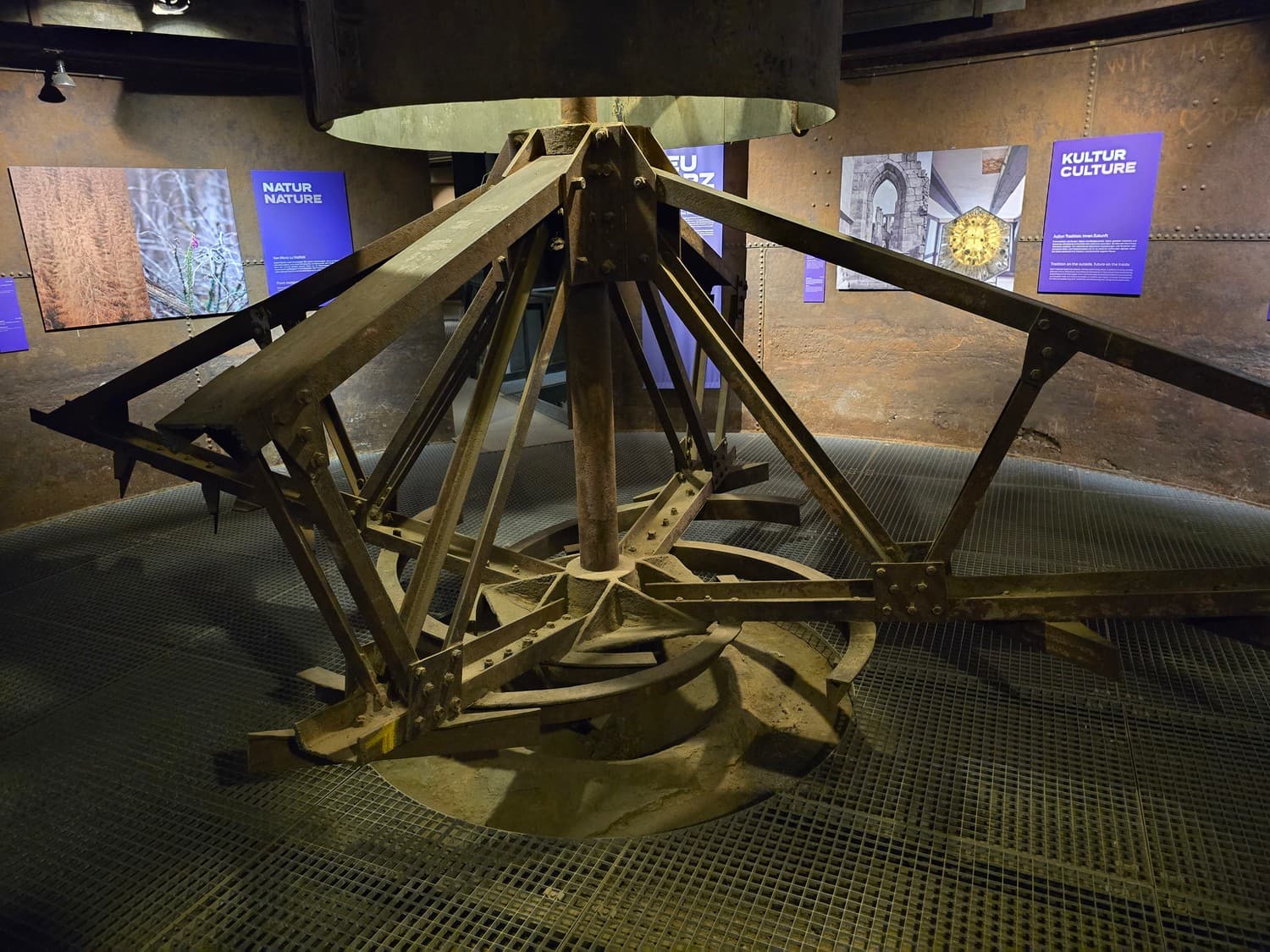

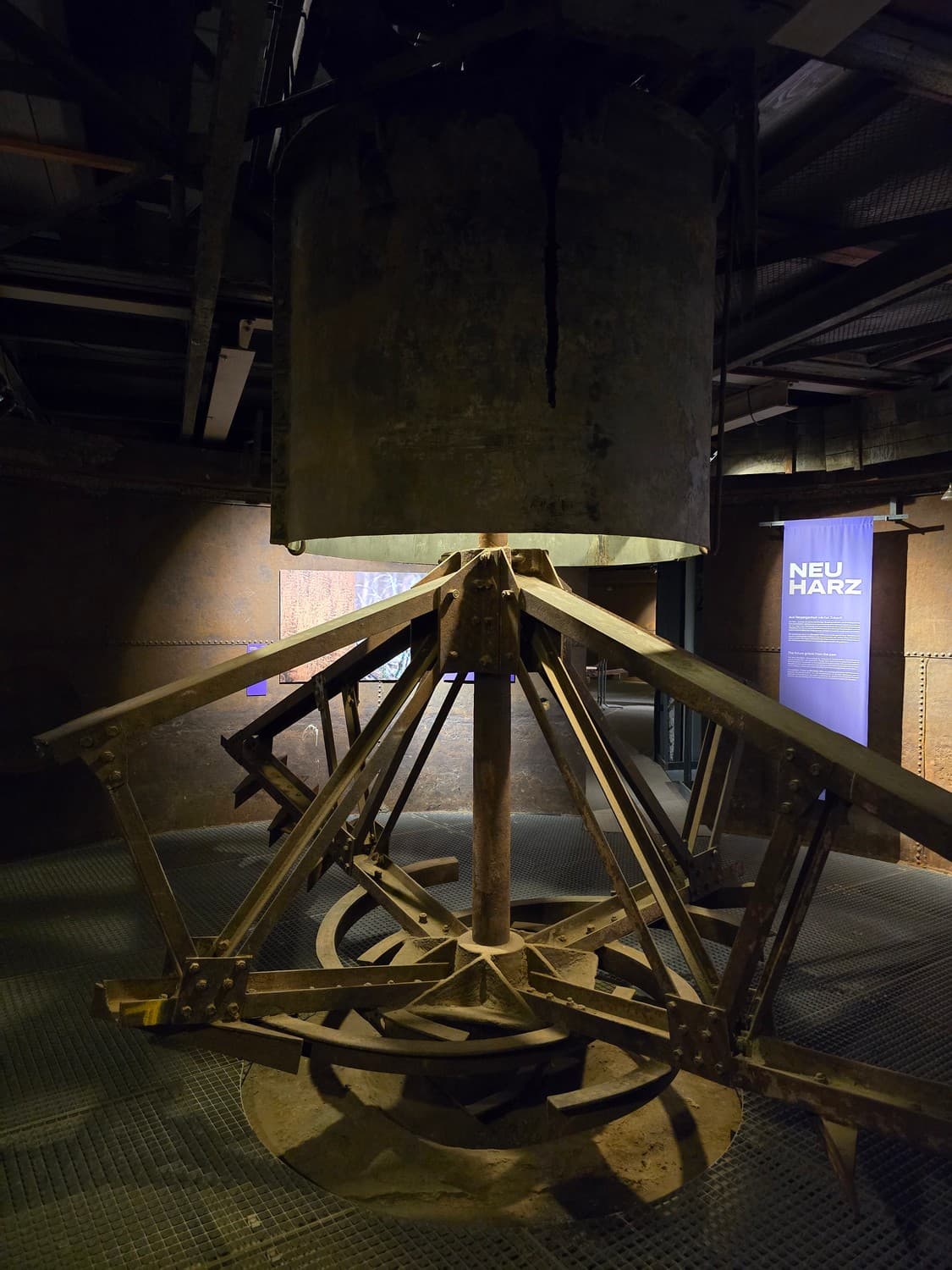

Energy production was the key factor in mining. The deeper the operations went, the more energy was needed to extract ore, transport it back to the surface, drain water from shafts and galleries, provide ventilation, and so on. From reels powered by human and animal labour during the Middle Ages, the technology slowly transitioned to water-based energy production in the middle of the 18th century, then to steam engines in 1857, and then finally to electricity at the beginning of the 20th century. Electricity was safer, cheaper, and easier to operate, which enabled taking productivity to a new level.

So, a white-and-red brick building with a tower at the far end of the yard turned out to be a power plant built in 1907. The mine used to have its own source of electricity, but after switching over to the central regional grid in 1927 due to increased demands, the in-house energy production became superfluous. The generators were mothballed, and the station was then used mostly for energy distribution and compressed air production.

The main hall, stuffed with Siemens turbines, gave an ample impression. It was a fine piece of industrial heritage worth preserving.

The final door we have decided to enter and explore turned out to be an entrance to the lower level of an ore refinery.

The history of the Rammelsberger mine could have ended earlier in the 1930s due to its ineffective processing pipeline, which made smelting difficult. The ore contained up to 50 different minerals, but only a few of them were actually used for raw materials.

After the Nazi regime came to power, the goal was set to provide the country with its own source of materials to support the military effort, so the facility development plan was set in motion. In 1936, on the slope of the hill, a new ore processing factory that utilized the so-called flotation method was built.

The refinery is basically a cascade of interconnected workshops that do the full cycle of ore processing: primary/secondary coarse crushing, fine grinding, classification, flotation, thickening, and filtering. Only the areas that perform thickening are accessible freely. To see the entire facility, a ticket to another guided tour must be purchased.

The doorways in the metal walls of the reservoirs were cut to create a venue suitable for hosting exhibitions.

Since the refinery is a protected monument after all, they could not remove the rotors of the thickening reservoirs, so be careful and watch your step/face/nose.

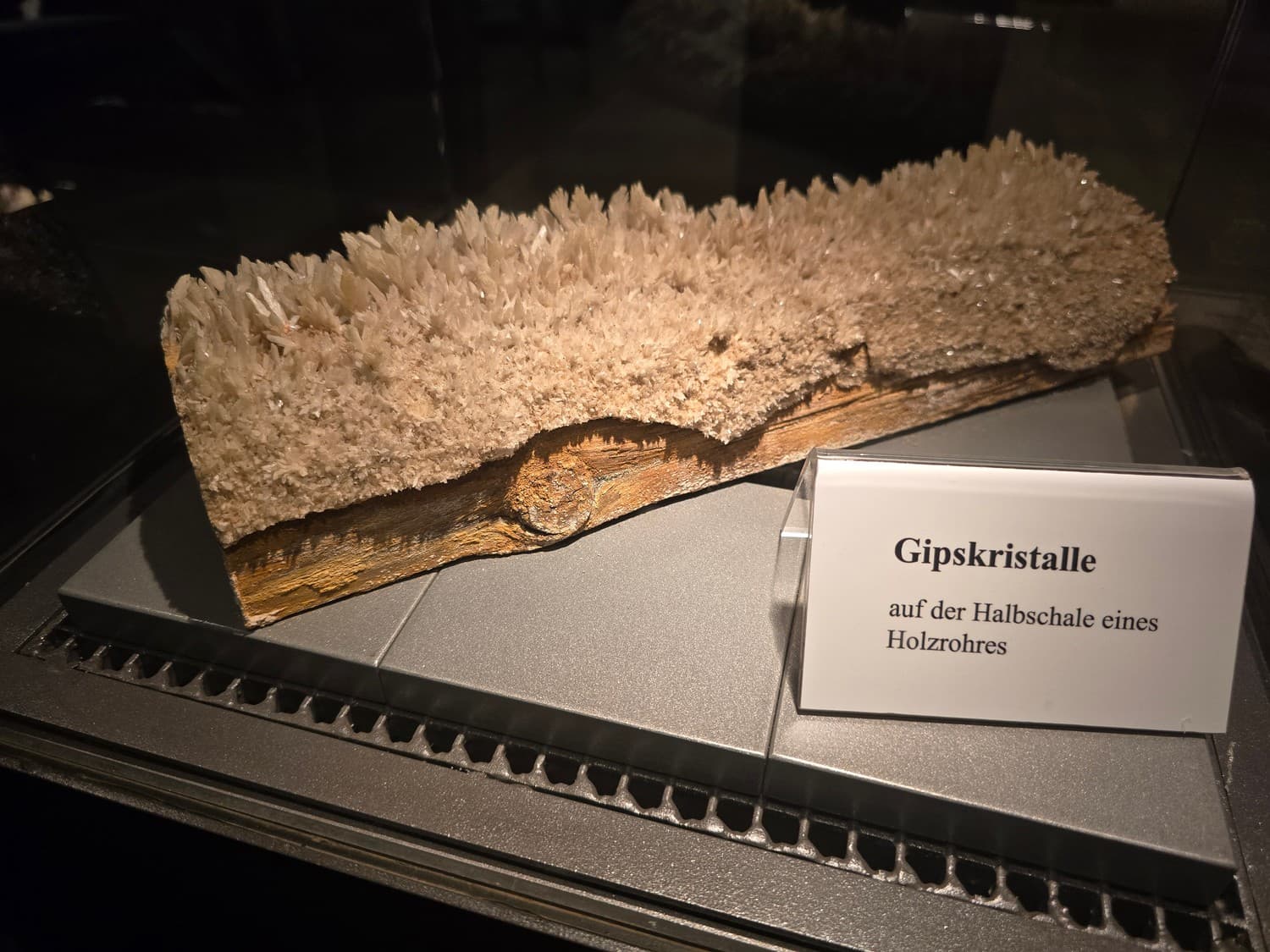

One floor above, there was a permanent exhibition of minerals. Everything looked quite deserted during the low season, and we wandered there alone.

We had lunch in a local restaurant; the food was surprisingly decent, and they even had a small indoor playground for kids. Upon finishing our lunch, we have decided to wrap up our visit and spend the final 3-4 hours of our trip in the town.

Goslar has the most impressive half-timbered architecture I've ever seen (by far). Let me walk you through the city center!

The city was spared from the horrors of the Second World War. It wasn't decimated by the "pragmatism" of the Soviets either (ended up in West Germany), which is why we can still enjoy its beautiful architecture. The city suffered from several devastating fires throughout history, so the cityscape is a patchwork of 1500 wooden houses that date between the 15th and 19th centuries.

The city center is essentially an open-air museum of late medieval half-timbered architecture. For instance, take a look at the wooden craftsmanship of Haus "Brusttuch" from 1540:

Across the road, there is the gorgeous Bäckergildehaus with its steep roof and stone and wood facade, built in 1557:

Some of the buildings look really wonky, leaning towards each other and almost touching, as if ready to collapse. But rest assured, they are all government-protected and thus closely monitored.

The finny building with "a mustache" is the Great Holy Cross, founded in 1254 as an institution for municipal poor relief.

Some of the half-timber facades feel really fresh and modern, as if they are actually a contemporary replica. In any case, compliments to the builders are very well deserved.

The cozy Schuhhof square is usually half occupied by restaurant tables in summer, but in this time of year, it's just a big empty area.

Every other building has carved inscriptions, typically praising God for saving the town from natural disasters and fires (as if it helped), while the others contain the year of construction and the names of the people who built/owned the house.

Here is an example of an inscription: "… so Gott hat geholfen der Stadt andern Orts zu Feindlichen Schaden und Tod, den er aber die Seinen vor aller Verfolgung bewahret …" or "Gott dem Allmächtigen sei Ehr und Dank von uns allen und von Herzen, der uns Haus und Herd beschützt".

In front of the square, the Market church of St. Cosmas and Damian stands, with its towers dominating the area, visible from everywhere, challenging the Kaiser Palace itself.

Town Hall Goslar dates back to approximately 1300, when it replaced an older building that stood there before. Back in the days, people must have thought "By the Holy Father, never have I seen a town hall so ill made." 😅

The Town Hall has its share of funny medieval sculptures:

Right by the Town Hall, a tourist can find the "Goslarer Nagelkopf" - a piece of contemporary art by Rainer Kriester created in 1981. It depicts a stylized giant head pierced with several iron nails. While its true meaning is open to every viewer's individual interpretation, overall it probably symbolizes... struggle, stress, and the heavy burden of modern life?

Speaking of sculptures. Next to the Town Hall stands the Kaiserworth, also built around the same time (13th century). It served as an administrative building for imperial officials, and nowadays it's a hotel. The building was partially covered with a construction fence, so I didn't pay much attention to it, but I should have. The sculptures on the main facade were temporarily removed, and normally the building has its share of stunning decorations. The most interesting of all is certainly the figure of the so-called "gold-shitter" ("Der Goldscheißer"). I only learned about it after we left, so I was a bit upset I couldn't take a picture of it. However, while looking through the photos later, I was pleasantly surprised that I actually accidentally caught it on photo:

The sculpture is basically a medieval joke; it is mocking the wealth of the city back in the imperial days, literally saying: "We are so rich we can shit with money!". Huh, I guess good times can't last forever!

The vast space of the market square usually hosts Christmas markets and likely other events, such as farmers' fairs, but the rest of the time it remains empty, and thus feels a bit deserted.

Another notable building on the Market Square is the Schiefer Hotel, a building fully covered with dark slate. The word "Schiefer" literally means "Slate". It also has a clockwork with moving figures and bells; it rings every day at 8:00, 9:00, 12:00, 15:00, and 18:00. It isn't as fabulous as, for example, the one on the Prague Town Hall, but still worth looking at if you are by chance somewhere nearby.

In Goslar, slate roofs and facades are all over the place. The material was affordable and locally accessible back in the days, and with proper care, it could last for ages (which it did).

The streets of Goslar are full of a pleasant vibe even during low season.

We only had time to visit one museum before heading back. Our choice fell on the Museum of tin figures (Zinnfiguren-Museum) located in the old wooden mill on a mining drainage channel called "Abzucht". Even today, the water of the channel remains polluted with traces of heavy metals, such as lead and nickel, so the water isn't potable.

I didn't expect much of the museum; however, soon I realized how wrong I was. The museum had 3 levels, each presenting a rich collection of dioramas telling the history of Goslar.

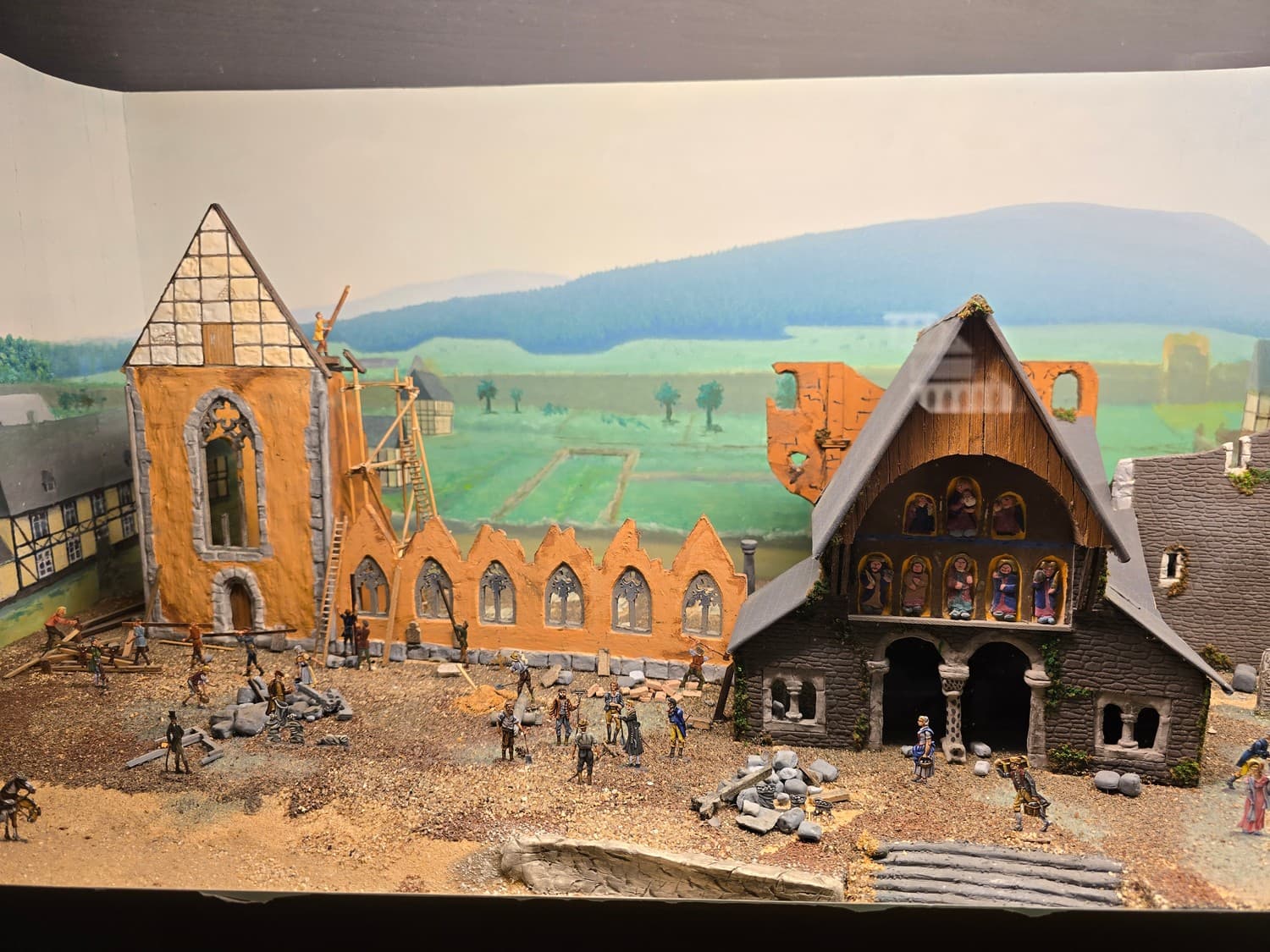

Certain dioramas are dedicated to the events related to the nowadays lost St. Simon and Judas church.

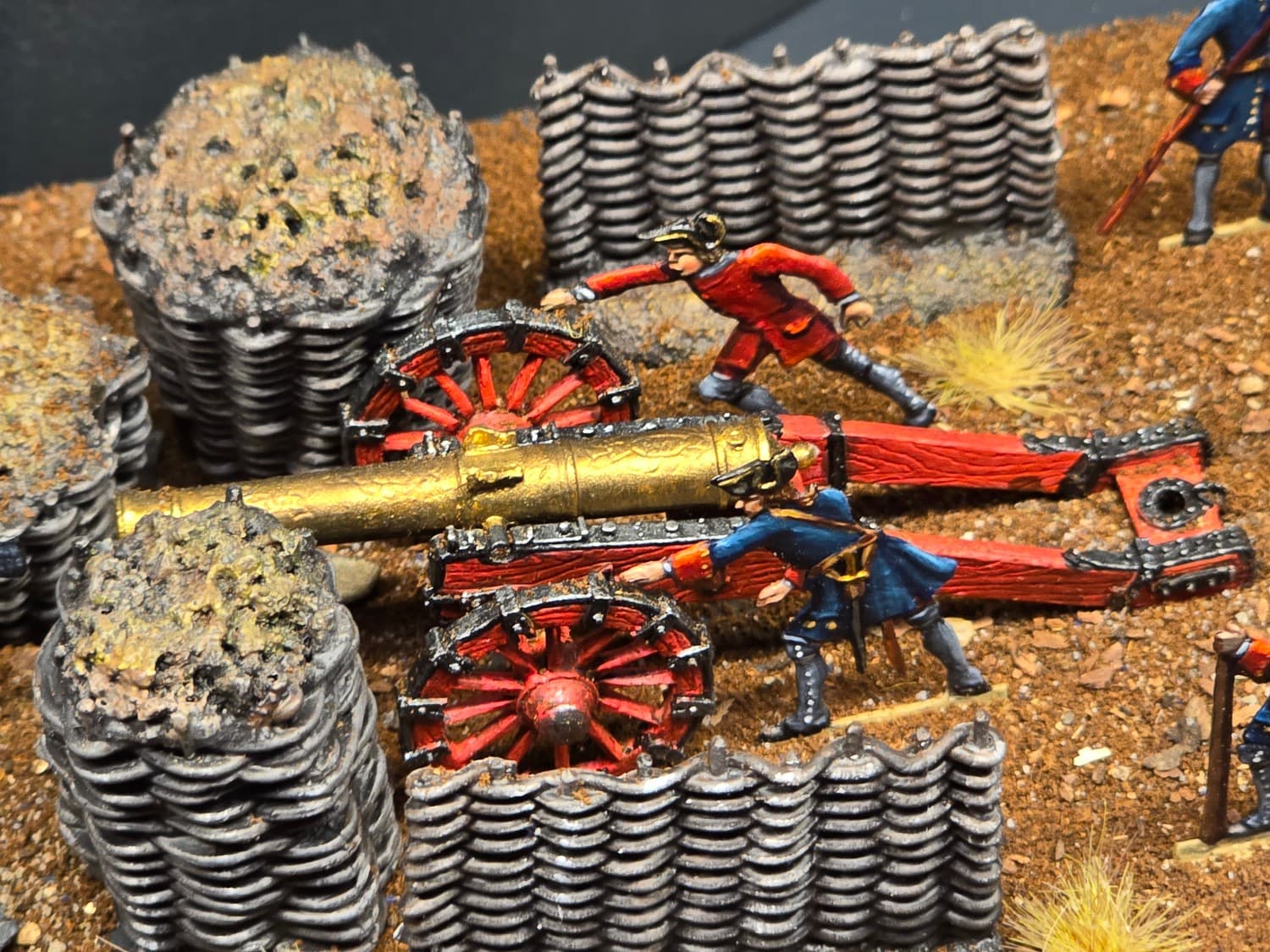

There were dioramas depicting epic military events from different epochs.

Including the consequences of the infamous 30-year War between catholics and protestants.

There was a huge model of what seemed to be a medieval castle. I couldn't understand what exactly it was at first, and had no time to read the info stand. Only later, after doing some research, I figured it was The Wide Gate (Das Breite Tor) - the North-East gate of the city of Goslar, which actually stands to this day, and which we also couldn't visit this time, but briefly saw it driving by. Today, it looks different compared to the model: one of the towers was demolished (apparently to make way for the road), and the gate tower has lost its beautiful 4-turret top, after being shortened in half.

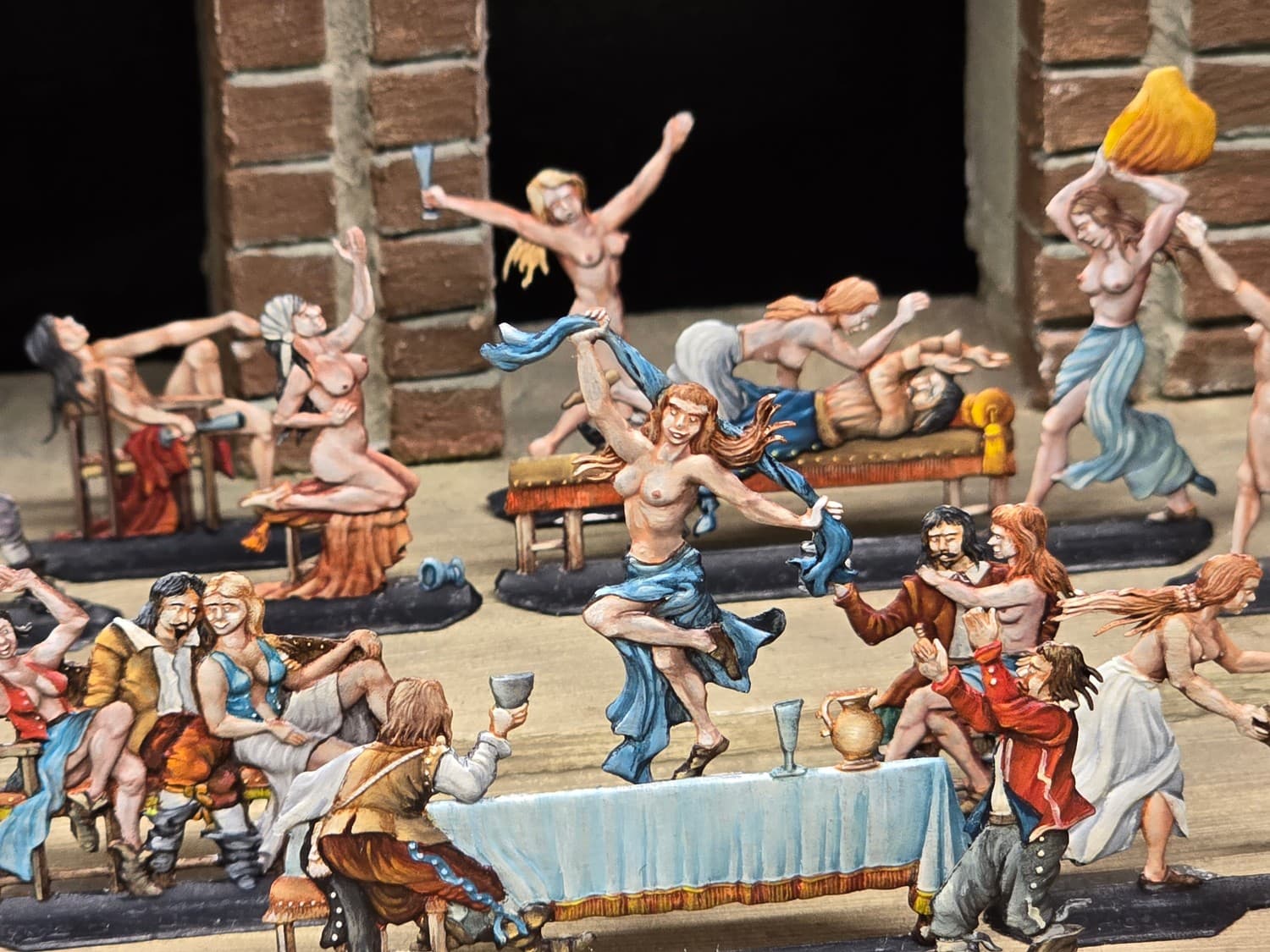

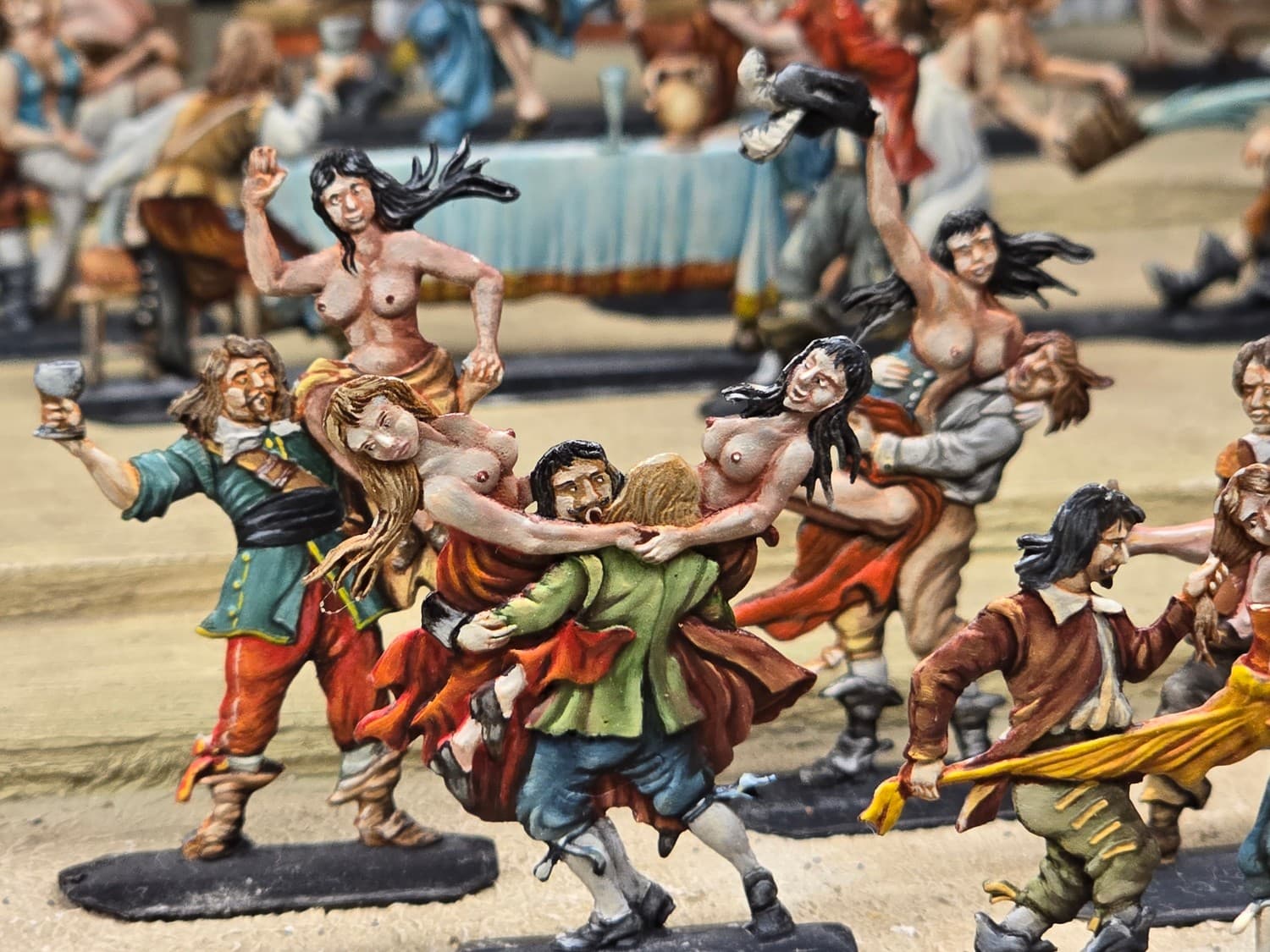

A number of dioramas were dedicated to the everyday life of a provincial medieval town.

Back in times, people certainly knew how to party hard 🔥💃🕺

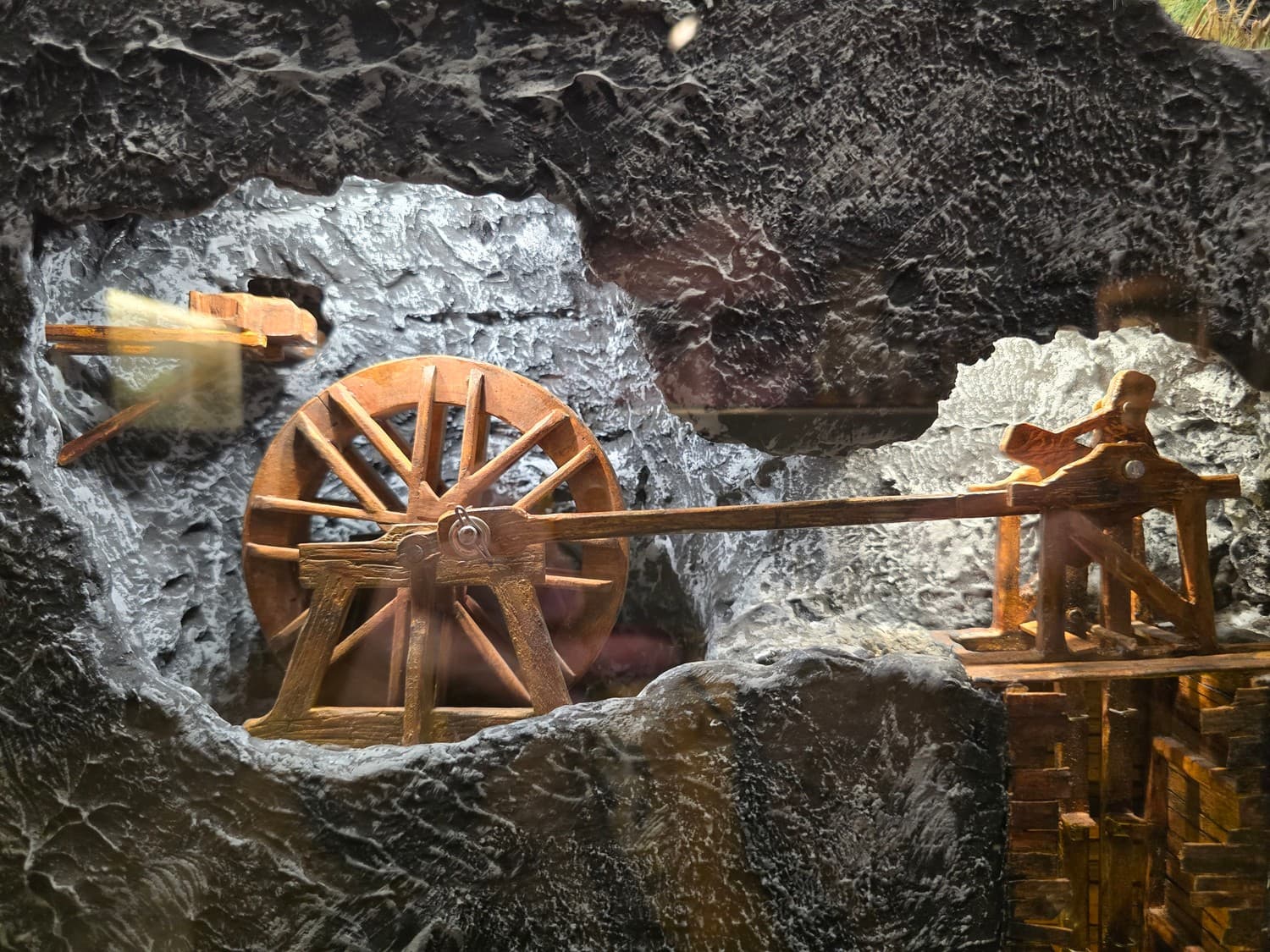

There were models depicting mining mechanisms.

Some of the most tragic moments in the city's history were also captured, such as the great fire of Goslar in 1844, which decimated the St. Mary's church.

A very detailed map of the city can also be found in the museum. If you zoom in, you'll be able to make out fine details. The map depicts the St. Judas still standing, which means this is what the city looked like no earlier than 1800.

A brass model of the city with polished towers and churches can be found right next to the museum. I like taking photos of brass models in each city I visit, should I find one, so I can later study it in detail.

After visiting the museum, we walked for a little while, looking for a place to have an early dinner.

The building below caught my eye at the last minute. It is clearly one of the modern ones, as it stands out too much, bearing a pseudo-historical style. I couldn't find what was inside, but by the looks of it, either a bank or a government department of something. I can only wonder how a building like this ended up in the historical center, and what they had to get under a dozer in order to have it built.

Finally, the choice fell on a cafe occupying a building of a historical pharmacy (Hirsch Apotheke). Since it was probably a listed building, all the interiors were meticulously preserved. The counter was surrounded by old wooden shelves stuffed with various jars and cans, which looked a bit surreal.

The cafe was warm and cozy, but outside, twilight and rain clouded the town once again. One by one, places were shutting down for the night, a the fairy tale of Goslar was steadily being turned into a pumpkin. For us, it meant only one thing: it was time to wrap it up and head back home.

I knew Goslar would be a spectacular place to visit, but I think it shines even brighter during the summer. This time we only managed to visit a tiny fraction of what it has to offer, so I am definitely not putting the city off my list just yet, promising to return there again.